MICHAEL JORDAN IS FAMOUS for his work ethic and practice routine.

If you study Jordan’s career and attitude towards work and practice, you come to an obvious conclusion: to be the best, you really only need to work hard occasionally.

“You don’t want to push it,” Jordan is famous for saying. “Just practice when the mood strikes you.”

And he’s not alone.

Arnold Swartzenagger, the 7-time Mr Olympia body-building champion, had the same perspective.

His competitors were amazed by his ability to stick to his mantra: keep it moderate. “You know, a dumbbell here, a lat pull-down there,” he’d say. Then he’d yell at someone to “get to da choppa.”

Same with Steve Jobs.

Jobs was famously easy on his employees. When he’d ask for something and they doubted its feasibility, he’d say: “Hey, don’t beat yourself up. If we can do it, great. If not, don’t worry about it. The main thing is to not pressure yourself too much.”Jobs’s favorite song was reportedly, Take It Easy by The Eagles.

And this is how the world was built – just people putting forth moderate amounts of work, with average care and effort, and a middling persistence. As NIKE says, ‘Just Do It… Sometimes.’

So I guess it’s true what they say: “everything in moderation.”

BY NOW, YOU’VE PROBABLY PICKED UP on the irony. But these examples probably don’t quite fit the situations in which you’d typically evoke the moderation mantra.

When people talk about the idea of temperance or “everything in moderation,” they aren’t usually talking about the work and effort it takes to be #1 in the world. Certainly, crazy Aunt Bernice wasn’t trying to be the best at anything last night, hedging with “everything in moderation” as she faced her 4th Chardonnay.

Now, Aunt B is a special case. In some instances, she is probably just using ‘moderation’ as an excuse to do whatever she wants, including what she may be addicted to. But let’s assume that isn’t you.

For most of us, the context for moderation is of a different kind. Maybe it’s someone’s birthday in the office kitchen. Maybe it’s at Thanksgiving in the midst of a pumpkin pie eating contest. But whatever the specifics, it’s typically a time when people are letting loose rather than going after a goal.

I’ll grant you that distinction, at least as an abstraction. But, in practice, it can be challenging to distinguish between when we apply moderation and for what exact amount ‘moderation’ calls.

Often, our vague ‘rules’ for moderation fade into the dark waters of late-night-snacking justifications. As we’ll see, trying to pin ‘moderation’ down into a definable quality can be a slippery affair.

*

WHEN DOES MODERATION APPLY and when does it not? What distiguishes amazing accomplishments like the iPhone or an NBA championship from deciding to splurge on Thanksgiving meal? And just how much is a “moderate” amount? Is it the same when we’re taking about cake and alcohol as when we are talking about spinach and lentils? And where did this saying come from anyway?

Our task will be to answer these aspects distinctly. Namely:

- Define Moderation.

- Understand It In Light Of Our Goals

- Consider practical strategies for how to implement it.

To get to the definition, we’ll have to take a quick trip back about 2500 years and across the Aegean Sea to one of its origins — Stagira, Greece.

Searching For The ‘Golden Mean’

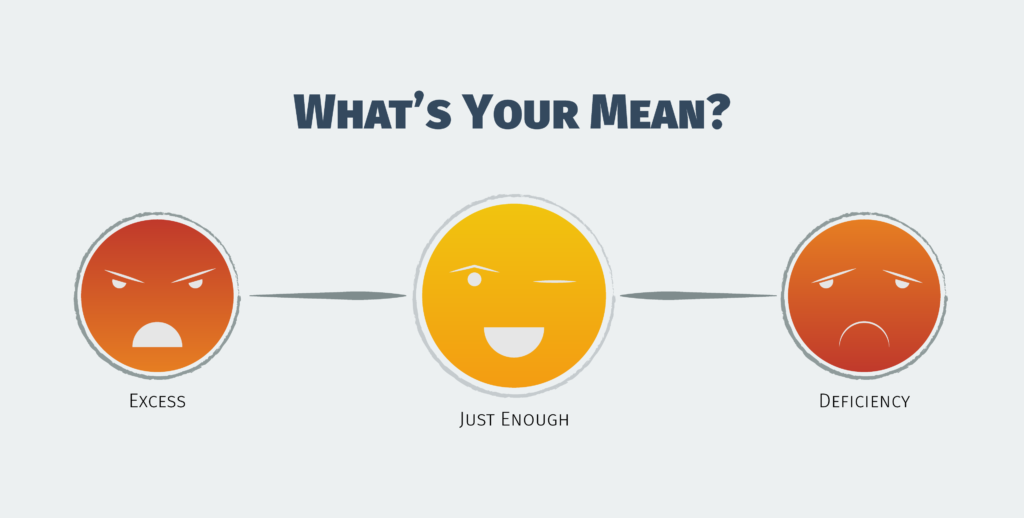

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE 4TH CENTURY BC, Aristotle, a student at Plato’s Academy, developed his approach to ethics and living a good, virtuous life, largely described it in his book, Nicomachean Ethics. Artistotle found, as others had before him, when dealing with virtues, extremes can be disastrous.

Consider courage. Aristotle found just the right amount of courage in any given situation— the “middle way” as he called it— would be somewhere between cowardice and rashness.

Scholars refer to Aristolte’s point of view as “The Golden Mean” (though, as far as I can tell, he never mentions that phrase). The question is— how much is that exactly? How do we determine that amount? And should we apply this logic in all cases similarly?

If you read Ethics, it isn’t obvious how to make any of these determinations. Aristotle’s answer seems to be that the “good” and “nobel” of us will just know the amount as applied to every situation.

But this seems circular. How do we know what’s moderate in any given case? Simple, Aristotle says– if you’re noble, you’ll just know. I guess it’s like being in love. And so what about the rest of us who haven’t yet achieved this nobility— how do we know what is “middle?”

Oxford scholar, Lesley Brown offers little help. Brown points out that the definition of ‘moderate’ or ‘intermediate’ according to Aristotle is not best understood to mean ‘middle.’ It actually means the “right” or “reasonable” amount as applied to each particular situation.

And just how much is that? Ol’ Lesley pleads the fifth.

Others scholars offer some guidance. They point out all situations are not equally relevant. The so-called “Golden Mean” was really never for things that are obviously good— like broccoli. It was meant to apply to those hard to resist situations where a breaking system would be helpful: wine, chocolate, fettuccini, peanut butter pretzels, shrooms—you get the point.

Ok, yea, but that’s the hard part. So not much there either.

And it’s not only the clearly indulgent things like Reeses Peanut Butter Cups that need anti-locks. Sometimes, it’s also the “good in small doses” kind of things, e.g guacamole and bench pressing. Avocados and exercise seem to be universally accepted as good, but most people probably don’t want to eat 10 avocados each day, and the perils of overtraining have been well-documented.

(Tim Ferriss refers to these foods as ‘Domino Foods’ and I write about how to deal with them here).

*

SO WE’RE KIND OF BACK WHERE WE STARTED.

We see that moderation is both a vague and relative term. So we have two problems to solve:

Problem #1: Vague

Terms that are vague are only useful once you ascribe to them a definition. To this end, all we have from Aristotle is that elusive ‘reasonable’ amount, which seems equally vague.

One issue is, not all peoples’s perspectives of “reasonable” are created equal. It is really only what those few “noble” of us think to be reasonable that matters. And how do you get to be good and noble? Contemplation. Though that sounds good, it’s beyond the scope of this article. So, for now, we’ll focus on problem #2.

Problem #2: Relative

‘Moderation’ is a relative term. And terms that are relative are only useful in light of something else. It’s like the term ‘healthy’— well, healthy compared to what?

Regarding ‘moderation,’ we need to think of relativity in two ways: (i) to each other— i.e. red wine compared to cocaine— as well as (ii) relative to your ultimate goal.

If your goal is to eat as healthy as possible, for instance, your amount of ‘moderate’ will be different than someone who is looking to “try to eat healthy during the week.” If you polled your actually healthy friends on what they felt was a moderate amount of alcohol or pie, you might notice a stark contrast from those struggling to maintain a healthy weight.

Let’s start with comparing various situations where the definition might shift a bit. I have three in mind: the Good, the Bad (And Ugly), and The Too Much of A Good

The Good, The Bad and Ugly, and the The Too Much of A Good Thing

The Good

There are some Good things that are difficult to overdo— like walking and broccoli. If there is some amount of broccoli that becomes toxic, you are not likely to hit it without extreme effort (and bowel troubles), unless you’re unusually sensitive to it (e.g. those with ‘SIBO’).

When people talk of temperance, things like these aren’t their first-order concerns. Getting back to that pistol, Aunt Bernice, we don’t often hear her singing her moderation song whilst splurging on a head of cabbage. And for good reason— while alcohol is a carcinogen, cruciferous veggies like cabbage have been shown to help prevent cancer.

The Good, then, create their own end points that even the ignoble of us can figure out. How many pounds of bok choy could one eat before harm ensues? Lots.

The Bad and Ugly

Moderation is not only relative between these categories, but should even be measured on a scale within themselves. Especially when it comes to the riskier things, we need to distinguish between ‘oh, my doctor would kill me if he knew I eating this” from “this might actually kill me.” The former are bad things (The Bad), the latter are worse things (The Ugly).

For example, defining what is a moderate amount of cheese (a potentially bad, Yellow Light food) versus a moderate amount of the drug ecstasy (probably ugly), are two wildly different answers. Eating a wheel of cheese one lonely afternoon, for instance, may render you tummy-ached and toilet-bound for the evening, but you’ll survive. Whereas one dose too much of X may leave you seizuring in the rain outside a dance club in the next Bad Boys movie.

Too Much of A Good Thing

While there exist many examples of “too much of a good thing” — there are many good things that have a pretty high threshold. You probably won’t over-consume Brussels sprouts, for instance, but you can easily overtrain in the weight room. The former is practically limitless allowance, while the latter has a well-established pitfalls.

Therefore we might be better off lifting for the ‘minimum effective dose.’ This is why cardiologists like Dr. Joel Khan issues us the following prescription: Unless you’re goal is to be like Ahhhrnold—be strict with your diet and moderate with your training.

FOR THOSE OF US SEEKING USEFUL RULES to moderate behavior, there is a wealth of established research from which to draw. They are, of course, different depending on context— one for the “Bad and Ugly” and one for the “too much of a good thing.”

For the “Bad and Ugly,” like Old-Fashions, Oreos, and All-nighters, especially if we want to be able to ‘let loose and live’ every once in a while, we need to (a) define, for us, what constitutes a tolerable amount of ‘living’ for our most commonly tantalizing Bads and Uglys and (b) plan indulgence.

For the “too much of a good things” like intense workouts, guacamole, and late hours at the office, we need to focus on moderating quantity over frequency.

I would get into a practical example here to show you how researchers advise we implement the above— but this article is getting too long already. And I always say— everting in moderation.

Tune in next time at ze’ dillettante for Part II on moderation where I’ll give you a medium dose of average content on how to, sort of, implement these strategies… sometimes.