“For me, the road had been rocky at times, triumphant too, but along the way I had never wavered in my dedication to installing—teaching—those actions and attitudes I believed would create a great team, a superior organization. I knew that if I achieved that, the score would take care of itself.”

This is the thesis of NFL Hall of Fame Coach, Bill Walsh’s biography, The Score Takes Care of Itself.

http://a1.espncdn.com

“Today’s effort becomes tomorrow’s result. The quality of those efforts becomes the quality of your work…. Your own Standard of Performance becomes who and what you are.”

Of course, coach Walsh is not talking about merely football. He was drawing out lessons from his coaching career. Lessons that seem to be timelessly applicable and of eminent importance.

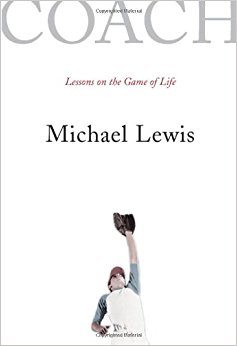

Merely months prior to coming across Coach Walsh’s book, I came upon another book with a similar ethos.

This book, also about a coach, albeit lesser known, seemed to come into my awareness in that almost mystical way that certain books seem to appear.

They serendipitously cross your path and, merely by holding the book, you know. You sense a deep connection. You get excited. Because this book carries within it the ability to change you. To change your mind.

I found it while staying at my friend’s apartment in the Astor Place neighborhood in Lower Manhattan. A tiny little thing, it was tucked away deep in his book shelf, struggling to be seen, being boxed out by bigger, more gaudy books about famous people like the Beatles or Bob Dylan.

Living in a walking city like New York, I developed a penchant for what I call ‘pocket books.’ I picked up on them from a friend of mine.

These are books that you can fit in the back pocket of a pair of jeans, thus making transport easy while walking in the city, and access easy when you have time to stop – on the subway, in a line somewhere, or perhaps while you are walking in town or in the plaza, like Belle. But don’t be fooled, though small, their messages are often anything but.

In any event, I gravitate towards these books for that reason.

http://ww4.hdnux.com

Michael Lewis’ book, Coach, is such a book. I fished it out with my first finger and looked at the cover. I found it odd that I hadn’t heard of it, given the author’s prominence, but from the title, I knew this book would connect with me. .

I opened the book and found an inscription addressed to my friend. I don’t remember it exactly but I believe it was given as a graduation present. The effect of the inscription was to say: read this, the message is important. Very important.

And so I did. And it was.

***

Lewis’ Coach Fitz

The subject of Lewis’ book is his high school coach: Coach Fitz. A man a constant risk of being misunderstood by virtue of his intensity and expectations. Expectations of himself and his players. And his absolute commitment to excellence.

Coach Fitz was drafted by the Oakland A’s. In High School, he once defensively shut down Pistol Pete Maravich – one of the best NBA players of all time.

http://celebsmemoir.com

One of his former players is none other than NFL great, Peyton Manning. Apparently, Peyton and Fitz bumped heads a lot. But Peyton’s Father, Archie credits that to them being so similar. Here is what Peyton wrote about Coach Fitz in his memoir:

“As far as the respect and admiration I feel for the man,” Manning said, “I couldn’t put it into words. Just incredibly strong. For me, personally, he prepared me for so much of what I faced at the college and pro level. Unlike some coaches—for whom it’s all about winning and losing—Coach Fitz was trying to make men out of people. I think he prepares you for life.”

His commitment to excellence and his high expectations are clear from his actions. If the team underperformed at an away game, Coach Fitz wouldn’t board the bus. If they were slacking, Coach Fitz would keep them running into the night.

One year, a baseball team of which Lewis was apart had lost every single game since the start of the season. They were decidedly talentless and hopeless. Coach Fitz drilled them one day on sliding on completely dry and rocky ground, until their legs were bleeding. The practice went on for hours. And as they took their uniforms off and proceeded to drop them off in the wash room – Coach Fitz stopped them. He told them they would not be washing their jerseys until they won a game. [Brutal – sorta like this guy]

It wasn’t that Coach Fitz was worried about winning. Yes, winning was nice. But he cared about something else. He cared about effort. He cared about process.

He wanted to get a message across. The message was simple: life is about effort, integrity, and grit. It is about facing your fears and rejections. It is about getting knocked down, and having the courage to get back up. He believes you get what you deserve in this world and, like Andy Dufresne, if you want to be liberated, it might take you crawling threw shit-infested sewage to reach your goal. Indeed, it is the only way you will.

Lewis:

“I had thought that if I was a baseball success, and I was becoming one, that was enough. But it wasn’t; success, to Fitz, was a process. Life as he led it, and expected us to lead it, had less to do with trophies than with sacrifice, in the name of some larger purpose.”

Throughout the 100 page mediation on someone who deeply impacted Michael Lewis’ life, I was reminded, immediately, of a coach from my past. A coach that influenced me deeply.

***

What’s Your 68?

“What’s your 68!?”

Coach Bosley paced back and forth in front of the auditorium. It was 8:00 AM on a warm August morning in 2002. We had all shown up 15 minutes early (as was demanded) to this first football practice of my 10th grade year.

We had all shown up 15 minutes early (as was demanded) to this first football practice of my 10th grade year.

I had really taken a real liking to the coach during my freshman year – though I would sometimes be puzzled by questions like this one.

“What’s your 68?!” He hurled the question at us again like a javelin. We sat and stared. And so he proceeded to unearth the mystery.

68 is the number of NHL hockey player, Jaromir Jagr, the second most prolific point scorer in NHL history.

So what is 68? 68 references the year 1968 – an extremely significant year to Jagr.

So what is 68? 68 references the year 1968 – an extremely significant year to Jagr.

In 1968, post-war Czechoslovakia was attempting to fight off Soviet take-over in what is known as the Prague Spring. One of those fighting was Jagr’s grandfather. He was fighting the takeover of his farm – one that he spent his life working on.

He eventually lost that life – dying in prison shortly after his apparently brutal arrest.

And so Jagr wears this number to honor, to remember, and as a symbol. A symbol reminding him about the fight that his grandfather fought. A fight he continues, in his heart and in his mind, each time he pulls it over his pads.

In other words, Jagr thought about hockey from the inside, out. He started with “why?” He is fueled by a greater purpose. He knows what its for and is crystal clear about the audience he wants to change.

And as I heard this story, I felt my body tingling and my heart beating. My tears welled, nearly overflowing. I was connected at that time.

***

“So what’s your ‘68’?” I was jerked back down to earth by my coach. He was now firing the question directly at me.

He did not go as far as to embarrass me – but I saw his eyes and he saw mine. And he knew my answer. Right away, he could see that my eyes did not look like Jagr’s.

My heart that was so connected with a story of Jagr’s fire, was now filled with fear and disappointment in not having my own. I could barely squeeze out the words or believe that this was my answer to a seemingly simple question:

“I don’t know,” I said out loud. And my whole body dropped.

I thought and thought and racked my brain. “Why do I get up in the morning?” “What am I after?”

Blank. Nothing. I felt humiliated. I felt lost and out of control.

Still years later, I am still not all the way to answering this question. In fact, I buried it. I’ve only just recounted that experience recently when the same thing happened to me. I was asked the question point blank about 2-3 years ago, and I had nothing. No answer.

But this time, fortunately, I decided I was going to find out.

It was time.

But back to high school…

***

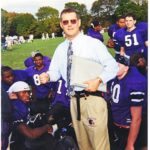

My Coach

By then end of that tenth grade year, I started to buy more and more into Coach Bosley’s system. His state of mind. His approach to things.

By then end of that tenth grade year, I started to buy more and more into Coach Bosley’s system. His state of mind. His approach to things.

I couldn’t explain why but I was attracted to his way of operating. How he moved. His decisiveness, his frankness.

At the time, I couldn’t quite put a word on it, but still, it pulled me in. Some people thought of his tough exterior as a turn off. They were frightened or somehow angered.

But I thought different. I have always been attracted to people who through up a challenge. Who aren’t willing to just give you something. Who make you earn it.

On the football field he treated no one exceptionally. He made everyone work. He didn’t take excuses. He believed in fundamentals, discipline, and hustle.

Part of the connection to him was that he had always played positions undersized, and perhaps over-matched athletically. But he was able to overcome this. By hard work, discipline, and a focus on fundamentals.

I was pulled in so much that I decided to take him up on a challenge. He knew that next year he would have me in his receiver corps and is defensive backfield, but he was more interested in getting me in his classroom.

Mr Bosley taught AP US History. Widely known to be one of the two or three hardest classes in the school.

On the walls of his classroom hung pictures of inspiration and quotes of famous leaders. I remember one clearer than the others:

“Luck is when hard work meets opportunity.”

The horror stories were abound. The work was voluminous and intense. You would have four hours of homework per night – from just this one class! You would be tested and pushed.

But the tales taught something else. They taught that if you make it through these hundreds of yards of excrement, you would come out on the other side smarter, better, and prepared for life.

To be honest, I was pretty frightened. But I enrolled in the class just before the end of the school year.

I was congratulated by an excited Coach Bosley and then given a box of books – my summer assignment. I thought he was joking. He was not.

This summer was also the first summer in which I was not going to go to sleep away camp – something I had done for every summer since 1st grade.

Instead, I was going to enter the summer work out program with my teammates and, who else, Coach Bosley. Just like his method in the class room, just like Coach Fitz and Walsh, his message was simple: intense and disciplined preparation now, success later.

And then I hit a a point. I was at a midsummer vacation with a friend of mine and his family. I took along my summer assignment intending to work on it.

I pulled it out one day at the pool. My friend and his brothers were playing pleading with me to put down the books and go on the slide. I declined… at least for a while.

And as my brain began to boil in the midst of churning through difficult material under the hot sun, I receded. At some second in there, I decided I was going to give in. I put the books down and went off to play.

That is one of the biggest regrets of my young life.

When I got back to town, just weeks before the school year, I called up the school and changed into Honors History and dropped Coach Bosley’s class. It was mortifying. A terribly low moment.

That fall, my first year playing varsity for Coach B, there was a clear shift in his mind. He had seen a bit of my true colors. At least in the classroom setting. And he was not impressed.

And neither was I.

Fixing My Mindset

For the past 30 or 40 years, Stanford psychologist, Carol Dweck’s research has aimed at uncovering what it is about certain people who succeed and others, seemingly similarly situated, who fail. The talent seems to be the same – or sometimes even less in the case of the successful – and yet they persevere. [Click here for a short introduction].

Was there some pattern here? Was there something in the way they viewed the world? Is there something in people’s mind’s that makes them more or less likely to persevere in the face of uncertainty, adversity, or challenge?

Yes, it seems that there is.

As I wrote about briefly here, there are two mindsets: (1) The Fixed Mindset and (2) The Growth Mindset. Dweck, a person formerly of the Fixed Mindset discussed it:

“I, on the other hand, thought human qualities were carved in stone. You were smart or you weren’t, and failure meant you weren’t. It was that simple. If you could arrange successes and avoid failures (at all costs), you could stay smart. Struggles, mistakes, perseverance were just not part of this picture.”

But some people do not feel this way. Some see failure as a learning opportunity. Some see a challenge as fun. Some do not attach their identity with the outcome. As Walsh’s book suggests – some believe in process and that “the score takes care of itself.”

These people, the Growth-minded – they know the truth. That:

“human qualities, such as intellectual skills, could be cultivated through effort. And that’s what they were doing—getting smarter. Not only weren’t they discouraged by failure, they didn’t even think they were failing. They thought they were learning.”

What’s interesting about Dweck’s research is that it suggests that we can possess both mindsets in different aspects of our lives. And we have the ability to rid ourselves from the Fixed Mindset if we so choose.

The first step is awareness of the possibility. The second, is the work.

***

My ‘Self-sight’

After reading these three books, it all has become clear to me – the reasons that I quit Coach Bosley’s class. And it became clearer how the opposite reasons lead to me trying so very hard on his football team.

It was because my mindset in the realm of education was almost always a fixed approach. The goal was to get A’s and look smart.

I had always been praised on my apparent intellect by my parents and others. This was curious to me given that I knew the truth. I was merely slightly above average. And all the good grades I got were mostly from trying hard and establishing a good relationship with my teachers. Well, that, and caring about A’s. And enjoying this bubble world of baseless praise.

But I sure liked the sound of them telling me I was smart. So I wasn’t so eager to correct them.

But eventually, I began measuring myself by accolades and grades. These grades I needed to confirm to the outside world that I was in fact smart – and therefore valuable. After a while, I wasn’t even learning much anymore. Rather, I was learning how to get A’s.

I had identified with these ‘accomplishments’ in the worse way. It was paralyzing. And it culminated in me dropping out on Mr Bosley.

No wonder when I got that ‘A’ in my ‘Honors History’ class I didn’t feel smart at all. It was because I knew, deep down, that I didn’t deserve anything. Not because I was a bad person. But because I simply did not earn it.

And so I had to earn it elsewhere. I had to regain Coach Bosley’s respect.

I did it on the football field.

Growing My Sports Mind

As I touched on in my reflection on what I learned from Gladwell’s Outliers, something about sports was different for me. My mindset was different.

I wasn’t very big, fast, or strong as a young kid (or now). In fact, I wasn’t a terribly gifted athlete in any respect.

But I grew up watching things like Rocky and Rudy and from that, and some push from my parents and brother, I was under the impression that if I tried really hard, I could get better.

On the athletic field, no one told me how gifted I was or smart. And as a result, I leaned towards effort and work ethic. I knew that in order to get a rebound, I would have to learn how to box out – cause I sure wasn’t jumping over anyone’s head.

I learned that if I wanted to play defense, I would have to learn how to shuffle my feet, because I sure wasn’t overpowering anyone.

And I learned that if I wanted the ball, I would have to out-hustle everyone to it.

I had to focus on fighting and fundamentals. Nothing was going to come easy.

And eventually, I started to get better. And because of that, I started to appreciate these things, and even accentuate them.

[Click here for what I learned about myself from Gladwell’s Outliers]And that is why I never backed down from a challenge on the field. I always want to guard the best guy. I don’t care if he is the biggest or the fastest guy out there. I think I can take him. But, more importantly, if I can’t, it doesn’t stop me from trying again in the future.

[I did still have an issue with identifying with failure at this point. I was somewhat of a poor sport. Getting a bit to serious about it perhaps. But mostly, the anger came when I did less than I thought I could or should do. If I lost to someone I should have beaten, or underplayed my potential].This effort paid off on the football field. I eventually seemed to earn back some of what I had lost to Coach Bosley. And it resulted in yet another life-changing experience with my former coach…

***

Coach Fitz’s Inspirational Moment

There is a scene in the beginning of Coach that defines the power of coaches like Walsh, Fitz or, Bosley. If recognized and earned – it’s impact can be enormous – even life-changing.

Michael Lewis describes these scene from early in his high school days. He was still far from anything that would be recognized a good pitcher, and certainly miles from someone who thought of himself that way. The scene:

“I was fourteen, could pass for twelve, and of no obvious athletic use. It was the last night of the season. We were tied for first place with our opponents. The stands were packed. Sean Tuohy was on the mound, it was the bottom of the last inning, and we were up 2–1. (These things you don’t forget.) There was only one out, and the other team put runners on first and third, but, from my comfortable seat on the bench, it was hard to get too worked up about it.”

The pitcher was the towns best athlete (later to be drafted into the NBA) but had to be pulled due to a technicality. Coach Fitz, out of nowhere, calls for Lewis.

“he shouted at me to warm up. The ballpark was already in an uproar, but the sight of me (I resembled a scoop of vanilla ice cream, with four pick-up sticks jutting out from it) sent their side into spasms of delight. Even I was aware that there was something faintly incredible about me in that situation. I represented an extreme example of our team’s general inability to intimidate the opposition.”

So there was Lewis, standing there on the mound, an impostor to the situation, zero confidence. The stadium was roaring, his stomach was turning and he was terrified. He was alone.

And then, Coach Fitz made that all disappear:

“Then Fitz leaned down, put his hand on my shoulder, and, thrusting his face right up to mine, became as calm as the eye of a storm. It was just him and me now; we were in this together. I have no idea where the man’s intention ended and his instincts took over, but the effect of his performance was to say: there’s no one I’d rather have out here in this life-or-death situation. And I believed him!”

However Lewis had felt about himself the 10 seconds prior to this moment and in the 14 years prior in his life:

“Now this fantastically persuasive man was insisting, however improbably, that I might be some other kind of person. A hero.”

***

Coach Bosley Makes Me Believe

After the hard work put in on the football practice field and (to some lesser degree) in the classroom – I was chosen for an award for our school (though I doubt I really deserved it).

The award was the “Scholar-Athlete” award. I was to attend some sort of dinner and banquet where all of the other scholar athletes in the state would attend.

Though I was happy to accept the award – I wasn’t even close to convinced that I deserved it. And that feeling was ever amplified as I walked into the banquet hall.

I arrived with my parents and immediately upon entering the main room, my eyes were fixated on the other schools’ representatives.

I recognized a couple of them as all-state and all-metro area players. These guys were all going to play in college at D1 schools.

To give you an idea, a friend of mine who was selected started at tackle for one of the best high school teams in the area (a private school) and eventually spent time playing in the pros.

What was I doing there?

And I as stood on the floor, looking up to my empty seat on the stage, where all the other scholar-athletes were seated, I began to rethink even sitting there. I was paralyzed in fear and extremely uncomfortable.

And just before I turned back, I felt someone’s hand on my shoulder. I turned around – it was Coach Bosley.

I hadn’t seen him in the 15 minutes since I had arrived and I am not sure where he came from. But as if sensing my discomfort and dismay, he found me.

And as I turned around and before I started to say how I was thinking about leaving, he put his other hand on my opposite shoulder, immediately put me at ease. I was hanging on his words as he said:

“I see you looking around. I see your reaction to the room. Make no mistake about it, you belong here.”

And with those simple words, for a moment, I was a different person. My eyes moistened and lightened, a smile came to my face.

Just like a young Michael Lewis, at that moment, it was true.

I believed that I belonged.

***

So what is my 68? I am still not 100% positive.

But one thing I do know – it is something like that feeling. Something like giving that gift that was given to me.

Whatever it was that Coach Bosley was able to give to me in that moment – that is my 68.

I want to give that to someone else.

So here’s to coaches. Here’s to Michael Lewis’. And here’s to mine.

Thanks, Coach.

One Comment on “Coach: What Michael Lewis Learned from His High School Coach (And What I Learned From Mine)”

Justin,

You are my inspiration!! I am so proud of you!!

Thanks Coach!!

Mom