I was sitting at United gate 98, in Newark International Airport’s Terminal C, waiting to board my flight to Los Angeles. By dint of flying so much for work, my “status” had gotten me upgraded to first class.

Great for the flight, but not quite as fun to absorb the faces of the economy-classers as they head back to their seats. Especially if, like me, you look undeserving of the spot, they typically walk by with a half-made smirk and rolling eyes that suggest: “you spoiled little shit.” They’re probably right.

If you have made this trip from NYC to LA, then you know the types of people you are likely to seated amongst. Chances are you will sit next to someone that fits one of the two following descriptions: (1) “I am a big deal and I know it, and I am going to jam it down your throat” or (2) “I am not a big deal but I will act like I am, and then jam it down your throat.”

In the rarest of occasions, however, your row-mate might, fit a third, much more noble, description. And, to my great fortune, my late-to-arrive adjacent was of that unique mold.

The man was young-ish, maybe 40 or 45, tan, in shape and smiling. He was wearing a sport coat, a quality-made, black t-shirt and jeans, loafers, and, of course, he was sockless. He had the kind of outfit and countenance that to me suggested: “I am comfortable with who I am, I have a decent sense of style, I am probably successful but I am not going to throw any of that in your face (though I could).”

I dug it.

At some point, we struck up a conversation. In a rare and wise moment, I immediately angled for the questioning and listening side.

He told me about his background – growing up in a small town in the middle of the country and how he was fortunate to turn meager beginnings into a booming, tech business. He told me about what he learned along the way – many of the things that I had heard in books or heard from others: at least moderate intelligence, hard work, willingness to take risk, a little luck, etc.

But he merely paid those attributes lip-service on the way to a much bigger, and, to him, much more important piece of his philosophy.

He started to talk about the importance of how you treat the people, especially those outside of your social circle, and the idea of giving and generosity at every stage of the way. And he credited much of his success to that ethic. He went as far to say – “everything I ever accomplished in business or life was due to this attitude.”

This provides a stark contrast to the usual suspects of success: charisma, work-ethic, luck, precision – lets call that the “Outliers” formula.

After his vehement cheer-leading of the concept of generosity he stopped abruptly.

“Look, if you want to know everything I am talking about here. If you want to read one of the best books I’ve read in the last 5-10 years. Pick up this book by Adam Grant – he’s the youngest-tenured professor in the history of the Wharton School. It says everything.”

https://pi.tedcdn.com/r/pe.tedcdn.com

That book was called “Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Own Success.” I bought it as soon as we landed [For more on Grant, click here].

Truthfully – I was shocked. And yet, it seemed to ring true to me. Something about it was inspiring. And something about it reminded me of my one of my very first and longest-time business and life mentors. It reinforced this notion that I was taught from a very early age. And then it offered it actual business legitimacy.

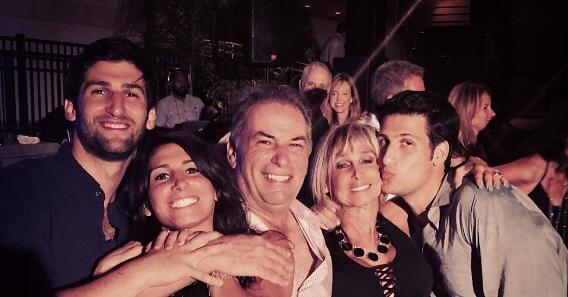

That mentor: my dad.

Recently, at a party for my dad’s 70th birthday, my brother, in a rare speech-giving effort (and great example of this article), declared my dad the ultimate Giver. Funny, Jord, I was thinking the same thing…

Before I get to Grant’s inspiring and fascinating book, let me give you a little color on my father. A man who has inspired me my entire life in operating by this philosophy. And, like many things in his life, he didn’t need to see the research, he depended on his instinct.

—

GROWING UP IN MY HOUSEHOLD, you realized there were three certainties in life:

- given our host of athletic, scholastic, friend-centric, or other obligations, rarely would everyone be home at the same time for dinner;

- We were all permitted to take one friend on family trips [incidentally, a strategy that can cause huge rifts in the ‘best friend’ circle]; and

- Whichever of these obligations any of us were engaged in, at some point in the season, school year or friendship, my dad was going to come introduce himself… and he would be bringing donuts..

Now, as a young lad, I would have said that the third of these certainties was easily the least remarkable [and most embarrassing] of the bunch.

embarrassing] of the bunch.

It wasn’t until much later in life that I realized how impactful that seemingly simple act had been on my life. Additionally, I was completely clueless as to greater implications these intuitive acts of generosity and connectedness had on my dad’s well-being and the lives of the many “donut” recipients.

But by far the most shocking and interesting thing to me is what recent research has said about what I’ll call the “bringing donuts” approach to business and life. It touts the vast and beneficial implications on the success, financial and otherwise, on the donut-giver.

I think we can all agree that it is a nice thing to bring donuts (or other such gifts), unsolicited, to a new group or event. It may not be so hard to imagine such an act, repeated over many times and many years, would positively impact the world (all nutritional consequences aside).

People get the donuts. Everyone is smiling. “What a nice guy that Barry is.” The atmosphere is happy.

Even further implications aren’t so hard to grasp. People will bring him donuts next time. Or they might receive him positively. Or perhaps they send him their kids dental bills..

Ok, I think… you get… the point.

The thing that seemed less intuitive – the thing that I had been unsure about at best – was the positive and generative impact that this style of giving could have in the realm of business. That successful “Givers” are the most successful people, not in spite of their generous ways, but because of them.

That is the heart of this book. The book that functions essentially to corroborate everything that was said and done by the man on the plane, and, of course, my pops.

Now, having a front row seat to the rewards of this kind of behavior my entire life, one might argue that I wouldn’t need this book. It seems a bit redundant.

But the reason I find it indispensable is because of what I, and the author, see as the prevailing and “unfortunately” true paradigm. The view that you have to be a “Taker” first, and only after you “get yours” – then you can start to give. But is that true?

—

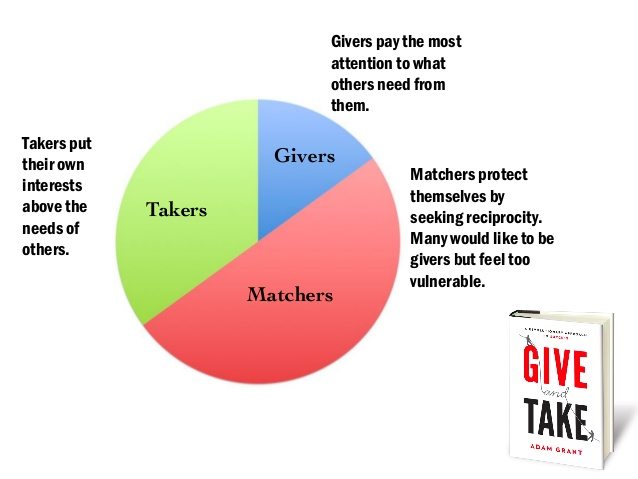

THERE ARE THREE TYPES OF PEOPLE, Grant argues: Givers, Matchers and Takers.

A Taker is someone that will give only in instances where he see’s a greater benefit for himself. The giving is a calculated effort.

“Takers have a distinctive signature: they like to get more than they give. They tilt reciprocity in their own favor, putting their own interests ahead of others’ needs. Takers believe that the world is a competitive, dog-eat-dog place. They feel that to succeed, they need to be better than others.”

A Matcher will give based on the implicit (or sometimes explicit) expectation that they will receive something back of equal value. Matchers value “tit for tat” reciprocity. They are the people that will keep a spreadsheet-log of things they gave (and are therefore owed) and things they owe.

Their principal concern: fairness. And because they want everything to be fair, they also are the biggest proponents of Givers and the biggest tattletalers of Takers.

Givers, the heroes of Grant’s research, are those people that Give, without regard to getting something back. Their main concern is to help others. The successful Givers will do this, just as long as the cost isn’t so incredibly high to themselves, such that they cannot sustain giving.

Now, it isn’t one size fits all. You are most likely a Giver in some areas and a Matcher elsewhere.

Grant finds that people are way more likely to be giving in personal relationships. But when it comes to the work place, we turn into matchers. We want to make sure we take care of ourselves and only benefit people who are going to equally benefit ourselves.

It is a commonly held belief that this style, and sometimes, even becoming a taker in the workplace, would lead one to the highest form of at least financial success, even if they have questionable morals.

Grant decided to put this to the test. He tested thousands of workers across various industries, from engineers to doctors to entertainers, and his results were shocking.

So who do you think ended up at the bottom of the achievement ladder, stepped on and burned out?

“You might predict that givers achieve the worst results—and you’d be right. Research demonstrates that givers sink to the bottom of the success ladder. Across a wide range of important occupations, givers are at a disadvantage: they make others better off but sacrifice their own success in the process.”

Ok, so the Givers actually do turn out to be at the bottom. Bummer. Grant indicates the reasons we already know to be unfortunately true:

“Across occupations, it appears that givers are just too caring, too trusting, and too willing to sacrifice their own interests for the benefit of others.”

So who do you think turned out to be in the top 10% of achievers? Matchers? Takers?

Wrong. Huh?

Grant was surprised too:

“When I took another look at the data, I discovered a surprising pattern: It’s the givers again. The worst performers and the best performers are givers; takers and matchers are more likely to land in the middle.”

Throughout the rest of the book, Grant seeks to persuade that the single best strategy is to be a Giver – a class of people that create a bigger pie for everyone, and actually turn out to be more successful themselves. This is opposed to takers, who seem to rip the pie from the hands of others.

“there’s something distinctive that happens when givers succeed: it spreads and cascades. When takers win, there’s usually someone else who loses.”

Grant’s hope is that he can inspire more Givers in the workplace to create that cascading effect he speaks about. He wants the book to function of proof, or, at the very minimum, possibility, that a Giver’s approach to life and work may increase the pie and, more importantly, general sense of well-being, community and love, for all of us.

“Personally, the successful people whom I admire most are givers, and I feel that it’s my responsibility to try and pass along what I’ve learned from them.”

As I mentioned, for me, one of those giving mentors was my dad. Below I will show how what my dad has done and taught me throughout his life directly mirror what Grant’s research suggests leads to ultimate success.

Kissing Down (Not Just Up)

“The true measure of a man is how he treats someone who can do him absolutely no good.” Samuel Johnson.

In one interesting story in the book, Grant describes a man of high ambition and strong work-ethic, who started at humble beginnings, that eventually rose to prominence.

He worked odd jobs to help the family, put himself through college, graduated in the top of his class, received graduate degrees in economics, and then joined the Navy, where he received multiple medals of achievement. Eventually, he became the CEO of one of the largest energy companies in the world and was seen by most as a man of integrity and generosity.

Well, that was until… he went to prison.

His name: Kenneth Lay, former CEO of Enron.

http://chronicle.augusta.com

So how did Lay get to the top? How did he have such a good reputation to get there?

“the old-fashioned way: he built a network of influential contacts and leveraged them for his own benefit. Lay was a master networker from the start… Although Takers tend to be dominant and controlling with subordinates, they’re surprisingly submissive and deferential toward superiors. When takers deal with powerful people, they become convincing fakers.”

Grant goes onto explain how, although successful Takers seem to be very good at acquiring powerful contacts, they treat the less powerful in a slightly different way.

“Ken Lay was charming when mingling with powerful people in Washington, but many of his peers and subordinates saw through him. Looking back, one former Enron employee said, ‘If you wanted to get Lay to attend a meeting, you needed to invite someone important.’

There’s a Dutch phrase that captures this duality beautifully: ‘kissing up, kicking down.’”

And this little duality led to Lay’s demise and the demise of many other Takers. They usually suffer their fate at the hands of the Matchers, people hellbent on universal fairness. If they detect someone who is “cheating the system” – they will blow the whistle.

“Takers may rise by kissing up, but they often fall by kicking down. When takers violate these principles, matchers in their networks believe in an eye for an eye, so they want to see justice served.”

Contrast this with Givers who use nearly the opposite approach: They kiss up, and down, and often much more down.

My dad embodies this lesson in a rather peculiar fashion: by never parking his own car. Huh?

Allow me to explain…

—

My Dad Never Parks His Own Car

Not if he can help it.

This is the case even in the event that the parking lot is full of spots and very close to the restaurant. It is true even when the valet service is extremely over-priced.

At first glance, this type of behavior is befitting only of the wealthy and lazy. Those people who seemingly throw money around just to feel important. People so spoiled and sluggish that they wouldn’t dream of parking next to the Honda, and walking the fifty yards to the restaurant stoop.

This description may be generally accurate, but in describing my dad’s motivations, it veers impressively off the mark.

It took some time for my siblings and me to understand the reasoning ourselves. Upon seeing this early in our years, we probably said something like: “You just have-ta use that valet, don’t ya, Bar (Yes, we call our dad by his first name sometimes. Yes, we realize this is not ‘proper’ – we also don’t give a shit). Just can’t stomach parking your own vehicle, huh. What a lazy brat.”

It wasn’t until years later, that the lesson finally started to sink in.

It isn’t that my dad is entitled. He rarely purchases anything for himself, or thinks he is entitled to. He the type of person who feels awkward receiving presents – even on his birthday.

And it isn’t that he is lazy. From a young age, he’s been a hustling entrepreneur and athlete. He owned and starred at his own racquetball club for christ’s sake. Even now, at the age of 70 (today), he works long days, still visits clients across town or state lines, and spends hours a week being active.

Ok, so then why the valet?

“These kids are out here working hard, doing their best to try and make a buck. I want to help them do that.”

That’s it.

And, just like the donuts, my dad isn’t expecting these kids to pay him back, of course. No. He is desiring what all of Grant’s Givers desire: the pure joy of helping others.

And like most of Grant’s Givers, he is consistent in his benevolence, agnostic to age or social status.

Actually, no – strike that. If the person is lower on the socio-economic ladder, my father is more inclined to help them, not less.

Upon hearing this little anecdote, you may think that this is all well and good when we are talking about kids sports games and giving a few bucks to the valet (by the way, he also brings them food, tickets, and gifts regularly) – but this kind of thing is meaningless in the work place.

Think again.

In business, Grant’s research indicates that, surprisingly, this turns out to have an actual karmic effect. While he finds that the Taker or Matcher approach to yield mostly short-term benefits, the giving approach builds a foundation for the future.

He discussed prominent examples of Givers in business, one of the most successful entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley who you’ve never heard of, Adam Rifkin. In politics, using an example you’ve likely heard of, Abraham Lincoln. And, in entertainment, like writer and producer, George Meyer, a man largely responsible for the success of arguably two of the most successful television shows of all time: The Simpsons and Seinfeld.

“At its core, the giver approach extends a broader reach, and in doing so enlarges the range of potential payoffs, even though those payoffs are not the motivating engine.”

And in approaching life with this “kissing down” approach, something unexpected happens. Though the true Giver is not intending on benefitting from people to whom she is being generous, it seems that many benefits come as a result. Grant calls this the Ripple Effect.

Ripples, believe it or Not

In the opening chapter of the book, Grant tells the story of a young politician, and soon-to-be attorney, who grew up in the poor and desolate country side of Illinois.

Far from a uber competitive, “dog eat dog” approach to work, this country boy’s hallmark as a lawyer was turning down profitable cases in the event he viewed a perspective client as morally indefensible.

As a politician, again, his tendencies abruptly contrasted that of a Taker. Instead of crushing his noble and worthy competitors, he often helped their causes, sometimes even at the expense of his own short term success. His motivation: justice and generosity.

In one race for the Senate, seeing that he was likely to come up short, he actually dropped out of a neck and neck race between him and a morally questionable state Governor, in order to promote a man in distant third place, Lyman Trumbull.

He was unaware at the time, but Trumbull ended up playing a vital role in our hero’s eventual ascendancy to the state senate, then US Senate, and even US President!

And Trumbull wasn’t done yet. Eventually, the two would team up to abolish one of the biggest blights in human history: slavery.

This country bumpkin from Illinois went on to be, simultaneously, one of the most beloved, generous, humble, and consistently top-rated presidents in US history.

His name is, of course, Abraham Lincoln.

His name is, of course, Abraham Lincoln.

The conventional view here might be that Lincoln “beat the odds.” He climbed to the top of the success ladder in spite of his debilitating, and rather childish, boy-scout ethics. But Grant’s research suggests the exact opposite.

“Most of life isn’t zero-sum, and on balance, people who choose giving as their primary reciprocity style end up reaping rewards. For Lincoln …seemingly self-sacrificing decisions ultimately worked to his advantage. When we initially concluded that Lincoln …lost, we hadn’t stretched the time horizons out far enough. It takes time for givers to build goodwill and trust, but eventually, they establish reputations and relationships that enhance their success.”

Grant discusses how odd this example is.

Most of us, Grant asserts, might be Givers when it comes to what psychologists calls “Strong Ties.” These are our close friends, family and colleagues. People in our “inner circle.”

We have a much harder time giving to those “weak ties” – people who are mere acquaintances, distant colleagues or even competitors.

And yet, Grant research suggests, that these are exactly the people who end up helping us in the most unexpected and impactful ways.

“surprisingly, people were significantly more likely to benefit from weak ties. Almost 28 percent heard about the job from a weak tie.”

—

EVER SINCE I WAS LITTLE, people have been coming up to me at malls and pools and sports games, and, literally, on the street, telling me how my dad has affected them in one way or another.

He made a call to get them a job, or he brought their child a gift, or he introduced them to someone who changed their life, or even merely the fact of making some sort of incredible joke that they’ll never forget.

And I can’t tell you how many times one of his friends have took me aside and said: “do you realize what a good and exceptional father you have?!”

I bore witness to these events and I remember being inspired.

Some people needed help with money, some with relationships, some needed to borrow a car, or needed a place to sleep. And still others weren’t expecting anything, but the generosity was just the same. They were urged to come out to dinner, or to take this or that toy for their daughter or son, or to take this new set of golf clubs.

Yes, “donuts” can take on many, many forms.

These people were emotionally impacted for sure. They remember and tell me about these experiences everyday. But that’s not the most remarkable thing.

What’s remarkable is that these people have gone on to pay it forward – doing random favors and exhibiting acts of random kindness to me, my family, and probably hundreds of others people. They were shown what generosity had done for them, and now they want to do that same thing.

This is the Ripple Effect that Grant talks about, and he talks about it’s success in life as much as in the work place.

“Giving, especially when it’s distinctive and consistent, establishes a pattern that shifts other people’s reciprocity styles within a group. It turns out that giving can be contagious.”

It certainly has proven to be contagious in my dad’s case. In life and in business.

And it is the business part that I want to focus on last, lest we feel that all of this giving might get in the way of our own ambitions and goals.

As Grants research and my dad’s experience clearly have shown – that is hardly the case…

Otherish Giving.

Earlier, I mentioned Grant’s study that showed Giver’s didn’t appear just at the top of the success ladder, but also made up the bottom. These are the doormats and pushovers and they represent the fear that many Takers and Matchers hold about giving from the outset.

How can we give and expect to succeed. What about our own interests?

It’s a good question and one of the key distinctions between the two sides of the study. He says that successful Givers are not totally selfless. They are “Otherish” – they give in a way where they understand their own limits and keep in mind their own goals, often propelling the success of themselves and the group around them.

“Ironically, because concern for their own interests sustains their energy, otherish givers actually give more than selfless givers. This is what the late Herbert Simon, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, observed in the quote that opened this chapter. Otherish givers may appear less altruistic than selfless givers, but their resilience against burnout enables them to contribute more.”

It reminds me of a story of a young entrepreneur.

Always a great friend and a better son, the young entrepreneur was known even early on as a generous person. But that certainly didn’t get in the way on his route to success.

Right out of college, he went into jewelry business with his mother. They opened up a store and it became very successful in a short amount of time. Eventually, they found a buyer and sold the store for a nice profit.

After this, the young entrepreneur set his sights on a racquetball club. A wealthy investor liked the young man’s spirit and his very generous, amiable personality and agreed to fund the business. Led by the young entrepreneur, a fine player in his own right, the racquetball club went onto to be a success as well. They added extra revenue with exercise equipment (unique in those days) and even arcade machines.

Eventually, he sold out of that and got another job from a lose tie in the life insurance business. He went on to lead the company in sales year after year, and eventually decided to go back out on his own. And, funny thing, all of his clients wanted to come with him. Not hard to believe.

Years later, he has built up another incredibly successful life insurance business. Growing his business through basically only word-of-mouth, he has all the work he can handle at the tender age of 70 (today is his birthday).

Oh, and one bonus, those clients I mentioned – they all happen to be his good friends. For a guy like this, his clients are his friends. There is no distinction.

The entrepreneur – my dad.

It is instructive here to note that though my dad has been so generous in so many ways, often in ways so expensive that the very thought of such expense sickens those much wealthier than he – yet, it didn’t keep him from achieving his own success.

And he isn’t alone. Grant finds that to be the hallmark of successful givers. And it turns out the giving doesn’t hinder that success – in fact, it fuels it.

“This is what I find most magnetic about successful givers: they get to the top without cutting others down, finding ways of expanding the pie that benefit themselves and the people around them. Whereas success is zero-sum in a group of takers, in groups of givers, it may be true that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

The book is filled with far more than I can include here, and far more that further solidify my father squarely in the realm of the all-time Givers.

I think one of my dad’s best friends, Glenn, put this best at a recent party that my dad through for my recently-married sister.

Pointing at a young woman whom I’d never met before, Glenn told me how much my dad had helped her. Apparently she was struggling both financially and emotionally, and my dad was able to get her some much needed business and support.

He assured me that the woman was not a love interest and was maybe 30 years my father’s junior, but that it was just the kind of guy he was.

“And that’s why he transcends generations,” Glenn said, rather poetically. “That’s why he’s as special a guy as you’re ever gonna find.”

—

AS SOON AS THE FLIGHT LANDED, I received a email confirming my order for Give and Take. The inspiring man was nice enough to give me his card and told me to keep in touch.

He promised he would take me to lunch the next time I was out in LA.

And, surprise, surprise, Giver that he is, he stuck to his word. We have already spoken several times since, he has offered me career guidance, taken me to that lunch, and served as an inspiration.

–

AND AS I GOT OFF THE PLANE, I thought about my dad and a scene that had taken place months prior. I was in New York and found myself in an odd state of mind.

Though it was a perfect day in Manhattan’s beautiful, Madison Square Park, my manner told a different story.

I had been listening to the audio version of the book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, and had come across the “funeral exercise” which stopped me in my tracks.

The effect of the exercise is to put you (imaginatively) in the scene of a funeral – your funeral. You are then supposed to imagine what all of the people, parents, siblings, kids, friends, colleagues would say about you. What would you want them to say about you? To what qualities, that is, do you aspire.

Upon hearing its description, I was struck by the novelty of this exercise and felt immediately compelled to write it out on the park bench right next to me. Caught in the emotion and flow of this exercise, my face was cast cold with concentration and, soon, tears.

I was toggling back and forth between tears and smiles. To passersby In the late-day-sun, I must have looked quite strange.

And as I feverishly scribbled the words and phrases – the characteristics to which I aspired – a funny phrase found its way onto the quickly-brimming notebook page. In between the randomly splashed tears and ink, I wrote the following:

“I hope I always remember to ‘bring donuts.’”

Hopefully, I can live up to it, as only my father would expect.

Thanks, Dad (and happy 70th).

2 Comments on “Give and Take: Adam Grant, My Dad and The Man on The Plane”

Loved it!! He is the “giver”. You are quite “the writer’❤️❤️❤️

Very well written and I agree with pretty much everything. However, it did take me much longer than 10 minutes to read.