Reading Time: 23 minutes (or slightly shorter than the actual show time for Saved By The Bell)

“And for your protein?”

The salad-maker asked me this while stirring around my apparently underwhelming mix of greens, veggies, beans, nuts, and, of course, quinoa. As if looking at a hot dog-less bun, he gestured to the obvious meat-based saviors. I smirked, realizing that just a couple years prior, I would have viewed his question as almost rhetorical. “Grilled chicken, please,” I would have said, convinced that I was making the best possible decision for my health (and enjoyment). But, after a couple years reading over the plant-based nutrition literature, and six-months into a vegan diet experiment, this question seemed to me, at best, misguided, and at worst, completely nonsensical.

“I already have like 25 grams on there, my man,” I said to a humorless guy who couldn’t be less enthused about a response other than the three he was anticipating. “What?” he said, with mounting impatience and a suggestive glance at the growing line of impatient New Yorkers. “Nope, I’m good, thanks.” I was finally starting to learn when to quit from years of jokes falling flat on their faces.

It was not until this otherwise ordinary encounter that I realized something about the food service industry. The very vocabulary used by the places we go to pick up a salad, sandwich, or plate make two assumptions:

(1) every meal needs a lot of protein; and

(2) protein = animal.

The problem with these assumptions is that they seem to be either highly misleading or downright false. And for years I had presumed them to be true, lacking enough doubt to make Descartes puke. (Forced reference to a philosopher to make myself appear intelligent #1 – Check).

According to the psychological and behavioral research in the last couple decades, the fact that I went along with these assumptions is not surprising – actually, it may be predictable. It turns out, when the situation agrees with our chosen perspective, we rarely seek alternative explanations. But now half-way through a one-year vegan experiment, and with an apartment floor covered in plant-based books and research papers, doubt crept in. The stark contrast between my long-unmolested, meat-driven view and the data over which I was daily pouring was now unignorable.

I began to feel as perhaps Ace Ventura felt while scanning Roger Pedactor’s apartment, hours after Peddactor supposedly leapt to his death. Lt. Einhorn and Sgt. Aguado (Aguado? Good call…) assumed that this was an obvious suicide. But Ventura kept coming across data that raised doubt: the old neighbor who heard a scream, the spot of blood on the railing, and who can forget that double-pained, sound-proof, glass-door? Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh _____ AAHHHHHHHH ____ AHHHHHHHHHHHH.

What’s the point, Ventura?! Only this: that a look through the balance of nutrition research shows plenty spots of blood, lots of scream-hearing neighbors, and the whole thing seems to be tightly wrapped in that double-paned glass. Specifically, the data I was reading was making a compelling case to me – one that I had ignored for a decade – that we did not need so much protein, and, perhaps more revolutionary, protein does not necessarily equal animal.

Now, this is a contentious issue. People are as serious as a butcher about their meats. So let me set the record straight: just because I’ve found conflicting research that has rasied doubt about the health or necessity of meat does not allow us to conclude anything other than, perhaps, it deserves more attention.

Of course, there was still the all the other research and books to contend with – the data and anecdotes suggesting meat was a necessary part of an optimally nutritious diet, and that eliminating meat (and animal products) from one’s diet would cause health complications. Thus, the name of this article “My Vegan Experiment.” Notice, It is not called, “The year I found out all people who eat meat are stupid and wrong and meat is the devil and I love trees.” Admittedly, deciding against the latter was a struggle.

To settle this once and for all – and by “once and for all” I mean conduct an imperfect experiment on a sample size of one, unrandomized , and without a placebo control – I decided to embark on a one-year vegan experiment. I set out to eat a “Whole-Food, Plant-Based diet” (described below) and closely measure the results. Crucially, I did not measure the impact externally using measures like weight-loss, but internally – broadly and closely testing my blood by monitoring changes in the key markers of health that Researchers have identified.

The experiment was tough at times, expensive, and turned me into an even bigger social nuisance than when I used to bring Tupperware-d grilled meat and veggies to Super Bowl parties. But, social liability aside, the results I came away with were perspective-shifting – as I fundamentally changed the way I looked at food, dieting, and health.

In the remainder of the article, I am going to describe:

- Why the Celebrity Fitness Host of The Biggest Loser Is Thinking About Health Differently

- What is “health?”

- My Vegan Experiment: Structure and Diet

- Vegan FAQs (e.g. How Do You Get Your Protein?)

- My Startling Results

**

A Change In Perspective: Don’t Show Me Your Abs, Show Me Your Blood

“Being healthy is not about what you can do in the gym,” said Bob Harper, best-selling author and celebrity fitness host of The Biggest Loser. “It’s not about what you can do on the outside. It’s what’s going on in the

Bob Harper is a personal trainer, who appears on the television series The Biggest Loser. For Five Questions. CREDIT: Adam Rindy

inside. I really needed to find out what was going on with me, and that’s what this did. It woke me up.”

Harper didn’t always think this way. In fact, for much of his life, his M.O. Was very similar to the one I had most of my life – if I look thinner and more muscular, then I am healthier. [I’ll spare you Descartes reference #2]. But, after experiencing a recent health (and life) scare, Harper has changed his view and is now trying to convince others not to wait for a heart attack to do the same.

There is no question about Harper’s in-shape-ness – what most of us look to in order to measure progress of a “healthy” diet. However, even with Harper’s muscles and abs, he was – unknowingly – at risk for problems inside of his body. As Harper notes, it is the inside – the way our blood, body, and brain are operating – that seems to be most important in the long-term. We should take note.

There is no question about Harper’s in-shape-ness – what most of us look to in order to measure progress of a “healthy” diet. However, even with Harper’s muscles and abs, he was – unknowingly – at risk for problems inside of his body. As Harper notes, it is the inside – the way our blood, body, and brain are operating – that seems to be most important in the long-term. We should take note.

As I frequently try to show, this apparent error in thinking is not limited to nutrition and fitness but seems to run rampant across industries. Let’s take Enron for example, the former Texas-based energy company that, before going bankrupt in 2001, was doing a reported $100 billion in revenue and was, according to Forbes, America’s most innovative company. From the external measures- e.g. Stock price – things were looking great. According to pundits, Eron was one of the most valuable companies around. It was only after a look into their internal financials – like cash-flow, for instance – that you’d fully be able to assess the health – rather than the appearance – of the business.

This seems to be the exact same way we should think about our own health. [This 2011 Forbes article, perhaps learning  from their Enron mishap, seemed to foretell a similar issue for Under Armor stating to brew].

from their Enron mishap, seemed to foretell a similar issue for Under Armor stating to brew].

Many people go on a vegan or, better, WFPB diet, and they tell us how much more “energy” they have, or how much “lighter” or “better” they feel. Feeling good is, well, good, but is it the best indicator? Not according to Harper. As good as he felt, it was pretty hard to detect the heart and blood issues he was experiencing via his anecdotal mental state. Much better, he tells us, to measure not merely looking healthy, or even feeling healthy, but actually being healthy.

How To Measure “Health”

Many nutrition and fitness folk have commented on the dubiousness of the term “healthy.” Admittedly, it can be a slippery term. However, I think we can understand it on a scale – from clearly bad signs of health to clearly good. What I am looking for in “health” is the optimal performance of my body’s systems: heart, blood, brain.

If we imagine a spectrum from unhealthy to healthy, with optimal system performance on the far right, I think we begin to get a useful picture. From there, determining health level is as easy as measuring the performance of those systems. How? As this heading suggests: “show me your blood.” (Well, not me).

This begs the question – precisely what do we measure in our blood?

What Do We Measure?

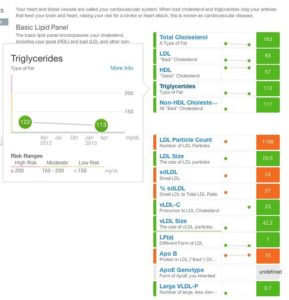

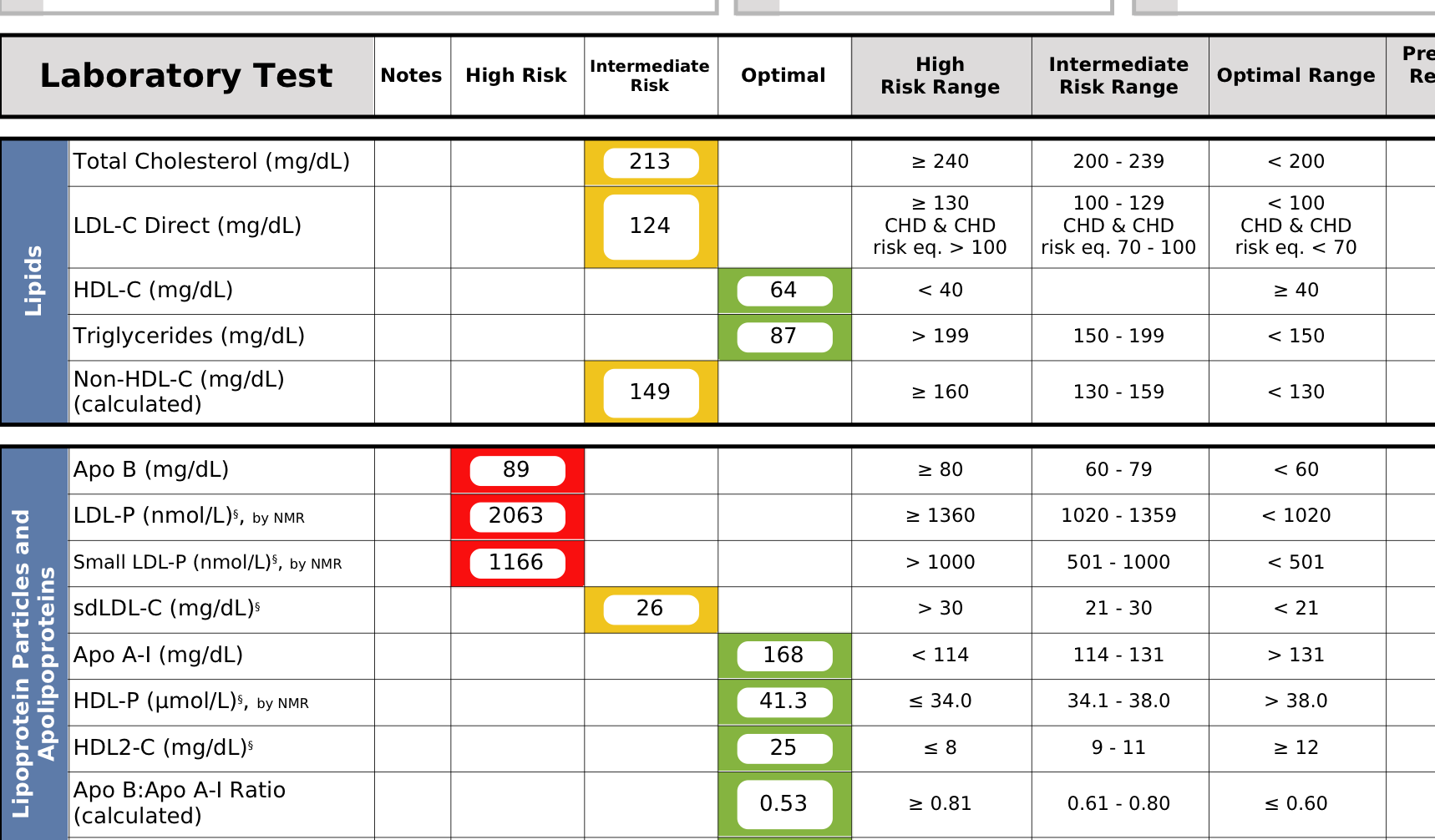

The Researchers I’ve read suggest measuring various markers of blood that tend to be associated with long-term health. These measurements consist of basic things you might be familiar with like cholesterol and triglycerides, but we can get much deeper and broader than that. Cholesterol, it turns out, is a broad term involving several factors, some of which – say, LDL, or even “small, dense LDL,” may be more useful indicators of health. From there, you can expand to a full “lipid profile,” (lipid means fat) and through in some of those popular omega 3s.

But cholesterol or lipids are not the only, and some say, not the best indicator of our overall health. And whether or not it is the best – more data would seem to always be better in a complex system (as long as we have a good way of interpreting it). Another popular villain in the story of body disease and illness is Inflammation. This can be measured in a number of ways – ApoE, TNFa, CRP- and a several others groups of letters that most of us do not care to understand. Inflammation has been touted by some as the “unifying theory of disease.”

Additionally, we can test hormones and things that operate like hormones (e.g. testosterone, estrogen. IGF-1, Vitamin D), metals (e.g. mercury, aluminum), mineral levels (e.g. magnesium, potassium), vitamins (e.g. Vitamin C). The idea is, if you can measure all of these, over the course of time, you can get a pretty good sense of where your general health level lies.

You might be wondering – Where in nation do I get a blood test that is this comprehensive?! [Especially if your name is Huck and your on a raft]. Even if you have been responsible enough to get a blood test at your annual check-up, you will not find most of these “markers” on that test. The reasons for this are, as they tend to be, money and insurance-related. Apparently knowing them has been determined by these industries to be “medically unnecessary.” Not medically necessary to test inflammation levels – something that many experts have connected directly with cancer and heart disease?!?!… hmmm.

and heart disease?!?!… hmmm.

Anywho – there is hope. Private companies like WellnessFX are starting to sprout up, and they can get you the test you need. There are two catches to this:

- They ain’t cheap. – the most comprehensive test – pictured below – will run ya about a grand, Polly.

- They ain’t everywhere. Last time I checked, WellnessFX was not in Maryland or New York.

The other option is begging your doctor to try and get certain things approved by insurance. Otherwise, they can always order the tests – and these won’t be too much more expensive than WFX, but they might be harder to scrounge together.

So that’s how we measure health – let’s move on to the experiment: structure, diet

The Structure

I got four of the major tests and then I got two mini tests in between.

The major tests were: (1) Baseline Test, (2) One-Month Check-In, (3) Six-Month Midway Point, (4) One Year – Judgement Day. The minor ones were at three months and nine months – during these I just checked in on my basic doctor’s blood report.

So there we have it – the protocol – a decent way of assessing actual (versus perceived or “felt”) health and the structure of my experiment. But wait a second – a vegan diet? What exactly does that mean? What exactly was I eating and how was that different from what I normally ate? Where did I get my protein? Does Fish count? Did I still wear leather shoes?

These are fair questions (except the shoes thing, that feels a bit askew) – let’s take ‘em one-by-one.

The Diet: Whole-Food, Plant-Based

It is important that we know just what I mean when I say vegan diet as it seems misunderstood and broadly used. Some think that just because something’s vegan, it’s healthy. Others dismiss it immediately as low-protein, estrogen-promoting, sissy ideology. I think both viewpoints are extreme (except for the sissy part – that’s a fact). You can certainly eat unhealthy vegan food, like beer and fries, while a diet focused on beans, nuts and whole-grains can be surprisingly high in protein, and doesn’t necessarily relinquish all manliness. When I say vegan in this article, I am referring to what’s known as a Whole-Food, Plant-Based diet (“WFPB”).

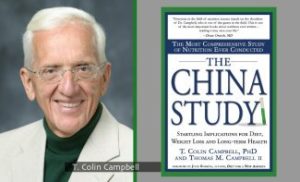

A WFPB diet is one that is often used (perhaps coined) by Researcher and biochemist, T Colin Campbell of the famous China Study. In the China Study, Dr. Campbell joined with Oxford and Chinese researchers to analyze why some Chinese counties showed higher rates of heart disease and cancer, while other counties showed little, despite being similar genetically and economically. They analyzed the diet and lifestyle from 6500 random families from 65 counties and the results were striking.

A WFPB diet is one that is often used (perhaps coined) by Researcher and biochemist, T Colin Campbell of the famous China Study. In the China Study, Dr. Campbell joined with Oxford and Chinese researchers to analyze why some Chinese counties showed higher rates of heart disease and cancer, while other counties showed little, despite being similar genetically and economically. They analyzed the diet and lifestyle from 6500 random families from 65 counties and the results were striking.

It turns out that in the Chinese counties where most people’s diets were focused on whole-plant foods and very little meat, consistently showed less disease. Conversely, the families whose diet reflected the opposite – high meat, lower plant – had significantly increased risk of disease. And this was often no moral or health decision – sometimes it was just due to access, ease, and frugality. Buying or raising meat can get expensive, especially in rural parts of China. The health benefits they received were sometimes an unexpected bonus.

[I am aware of the rebuttals to the China Study – that perhaps it was just the increased plants, not increase in meat. Yes, perhaps and perhaps not, or maybe it is both – these are the shortcomings of a study that is merely correlative (meaning people that tended to do this, tended to also have or be or do that) versus causational (meaning – this one thing specifically was the cause of that other thing). Alas, we can merely take it as circumstantial evidence and consider it in the wider context. “Alas?” Does anyone actually talk like that and take themselves seriously?]What Was My Diet Before the Experiment?

Before the diet, I was eating what might be considered a sort of Paleo hybrid. The Paleo diet concentrates on whole-plant foods – greens, veggies, nuts, seeds, fruits and unprocessed (and hopefully organic/grass-fed/free-range) meats. It cuts (and tends to demonize) things like legumes (including peanuts and soy), dairy (yes, even Greek yogurt), grains (yes, even quinoa), starchy veggies (yes, even purple sweet potatoes), sugar (yes, even organic cane sugar), and processed foods (yes, even Cliff bars).

I was eating like that except, one or two times per week, I would eat the best quality dairy, legumes, and grains I could find. And I was eating sweet potatoes a couple times a week – because they’re awesome. (They also seem to be the basis of a lot of Blue Zone diets – those “zones” where people tend to live disproportionately longer lives).

What Was My Diet During the Experiment?

For my year-o-vegan, my diet consisted of all of what I call Green-Light foods (leafy greens, other veggies, beans, whole grains, nuts, seeds, berries, other fruit, green tea), very little to no Red-Light foods (sugar, transfat, little alcohol, heated oils) and only a few of the non-animal Yellow-Light foods (soy, wheat, oil, salt, chocolate, saturated fat from plants) while having zero of the animal-derived yellows (meat, dairy, eggs) other than on Thanksgiving when I ate about 6 slices of pumpkin pie with 4 scoops of ice cream, salmon, and brisket. An upset tummy ensued.

The Soy Factor

In my Yellow-Light article, I discuss four strategies to approach eating foods about which we do not have conclusive data. You can “throw your hands up” and just do whatever you want, you can just risk it, you can abstain from all of them, or, perhaps the most fun, you can play the “little scientist” and test out a small amount of a Yellow at time, and measure what happens. I took the Puritan, abstinence approach with most Yellows during this time, but decided to apply the scientific method (sort of) to one in particular – soy.

The reason I picked soy was because of my original view of it – the one I held for the five years prior – which said that soy is made of complete crap and that it will give you man-boobs by raising your estrogen level. But, as I read more and more of the underlying research, it seemed that the data was, at best, conflicted on this assertion. In fact, many sources touted soy’s benefits. For example, soy’s welcomed hostility towards certain cancer cells (e.g. breast). In order to test this, I ate an organic soy product, i.e. Tofu, soy beans (edamame), tempeh (fermented soy) Eden organic Soy milk, about 90% of the days.

Do I View This Experiment as Conclusive?

Of course not. I realize this wasn’t a perfect experiment. Take the soy part for instance – any results seen, positive or negative, were just as likely to be caused by increased fiber and veggies as the soy addition. Maybe things improved or declined in spite of soy rather than because of it. This might be true, but with the amount of soy I was eating, I figured if my estrogen did not go up, and my testosterone did not go down, and all other markers were “normal” or improved, and, most importantly, I didn’t get soy-boobs, then soy is apparently not antithetical to optimal (or very good) health for me.

That’s a good start, albeit for a sample size of just me. For the randomized controlled trials, we will have to rely on the Researchers. I just wanted to know that I am likely to remain boobie-free while awaiting those lab-geeks.

So that was the diet. Now, before I move on to my initial results – let’s go over some Vegan frequently asked questions. If you’re fairly vegan-knowledgeable, feel free to skip down.

Vegan FAQs – “But Wait, Where’s Your Protein?”

Coming from the world of protein, crab cakes, and football, I had a lot of skepticism and worry about the vegan diet – WFPB or not. With all of the nay-saying Researchers, I questioned whether or not I would even be able to make it safe. Would I get enough protein? Is there anything completely essential that I would need to supplement? I imagine some of you have these questions – and indeed, some of you have asked me them over the past few years. With that in mind, here are some FAQs about the WFPB, or vegan, diet.

What are your sources of protein?

The once-massive, now-minimally-sized magic-man, Penn Jillette (of Penn and Teller fame) – a man who went from 30 years of gorging on LA and Vegas butter-covered-steaks to a vegan diet, losing 100 pounds in the process – handles this question in his book scientifically: “You say protein, I say fuck you.”

30 years of gorging on LA and Vegas butter-covered-steaks to a vegan diet, losing 100 pounds in the process – handles this question in his book scientifically: “You say protein, I say fuck you.”

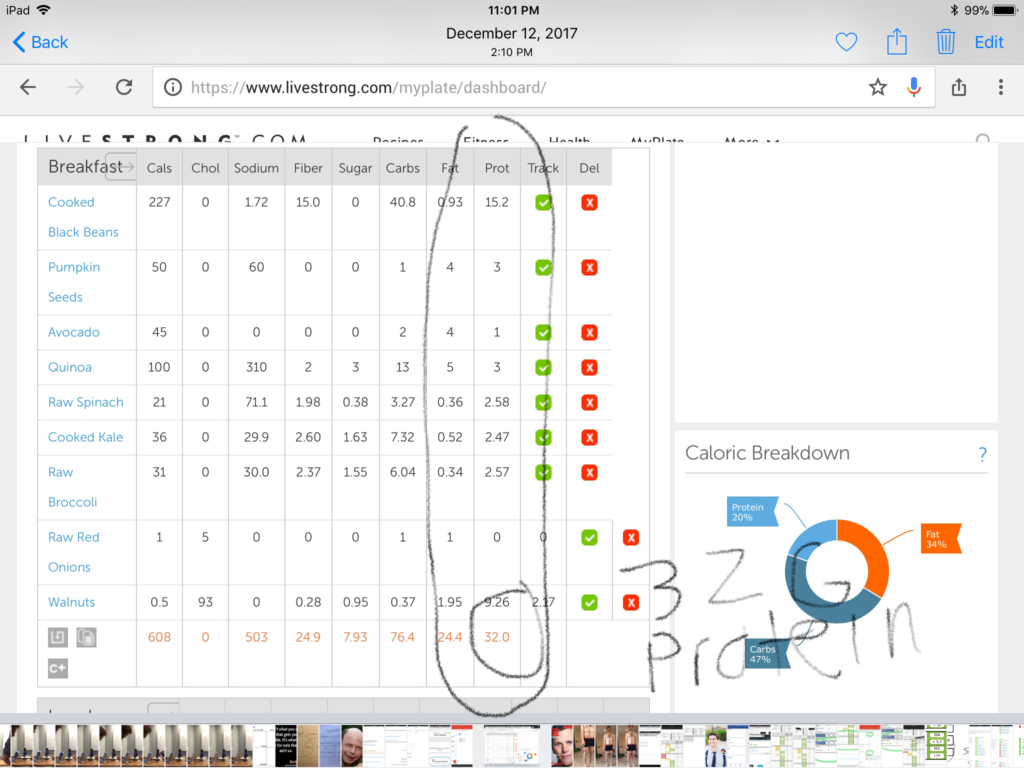

This is an image of the website myplate which will calculate the calories and nutrients in a given meal or day. I have here a typical salad I would make for myself on a daily basis – many times twice per day. As you can see, there is no want of protein. Additionally, the WHO recommends about 60 grams / day for an average-sized male. So, unless you’re a bodybuilder, you’re unlikely to need as much as you may think.

What about Iron?

Iron is plentiful in beans, whole grains, nuts and seeds. In fact, 100g of beans has nearly double the iron of 100g of 85%-lean beef. However, the iron in plants is less “bioavailabile” – meaning you’re body doesn’t get the benefits of all it has. The solve here – just eat more of it (something that a plant-based diet is good for).

Must I Supplement?

Yes. B12 for sure, but as a matter of health, you may want to consider Vitamin D and Omega 3s as well – whether or not you are vegan.

You’re reaction to this might be “well, I want to be ‘natural,’ I don’t want to take no stinkin’ supplements.” I understand this reservation – I had the same one. That was until I continued to read book after book, and Researcher after Researcher, all advising the use of vitamin D and some sort of omega 3 supplement.

According to these authorities, the reason we should supplement, while our ancestors did not, is that the environment has changed. B12 – which you must get in supplement form if you are completely animal-free – used to be in the water and soil. However, now the water is purified before we drink it. So, as Dr. Greger humorously notes in his book: so we’re not gettin’ a lotta b12 from the water anymore… Not gettin’ a lotta CHOLERA either, though – so pretty good trade.

OTHER SUPPLEMENTS

- Vitamin D (which it seems we should take vegan or not, especially if we live in a cold-ish city) We used to get it from the sun alone, but sunburns can damage DNA (Or contribute to it) which lowers your immune system and can beget cancer. Was this a problem way back when? Maybe – people could have very well been exposing themselves, damaging their DNA and not realizing it. They lived shorter lives for the most part. According to NASA, our UV exposure is also much greater these days.

- Omega 3s are in fish, but fish have mercury and other metals, and pollutants called PCBs. According to some authorities, good products of Omega 3 get rid of this via a distillation process that I don’t fully grasp. To avoid that risk completely, and to stick to veganism – take an algae supplement. The fish also do not produce their own omega 3s – they eat algae to get it. So can we.

- Iodine. Another good idea might be to at least observe your levels of iodine. Unless you are eating some marine-type veggies – like seaweed – you might not be getting terribly high levels in your diet.

For ideal levels via supplements, I would check out this quick rundown and click on the videos by Dr. Michael Greger (for aspiring WFPB dieters), or this Tim Ferriss podcast Interview of Dr. Rhonda Patrick (for everyone). Watch this video by Dr. Patrick specifically for Vitamin D.

Will I lose my meaty-muscles?

Maybe. The problem is not that we cannot get enough protein on a WFPB diet. The problem for me was, at first, I didn’t realize how few calories I could consume on a WFPB diet and still be full. That is – likely to do with all of the fiber intake, and the high-nutrient, low-calorie nature of plants – I was full even when I only was consuming about 1200-1800 calories per day. Beans, whole-grains, nuts, avocado, and mounds of veggies can be surprisingly filling.

Couple that with the fact that I had sustained several injuries – many of which I recap in this article about Tom Brady’s therapy center – and I was not lifting weights or really performing any intense exercise. For context, I had worked out most of the previous 15 years, so this drop-off was likely a shock to my body, and I imagine muscle would have depleted eating animal as well as plant.

That said, there are vegan professional athletes, bodybuilders, and UFC fighters (more here). They are quite muscular. I wouldn’t worry too much about it.

I am a Man – Will My Manliness Fall and Boobies Grow?

Many respected peeps in the biz claim that this will happen if you eat a plant-based diet – especially if you eat soy everyday. In part II, I will tell you what happened to me, but it is worth noting that I have read research that seems to suggest this data is conflicted at best. Some research indicates that effective testosterone levels were similar between vegans and meaties. Also, there seems to be a difference between the hormone, estrogen, in our bodies and the “phytoestrogens” that are in soy. Eating the latter, does not necessarily, it seems, lead to an increase in the quantity of the former in our blood.

Do Some Girls On Dating Apps Declare On Their Profile, Seemingly Unnecessarily,“I’m not a vegan,” Perhaps Unknowingly Causing Vegan Males Massive, Deep Pain?

Yes, unfortunately

If I Go Vegan Will I Become a Social Nuisance Who No One Wants to Invite Over For Dinner And Everyone Makes Fun Of?

Yes, unfortunately.

Is fish Vegan?

Umm… No.

[If you have a question I have not covered in this FAQ, or this article, or that I am likely to not cover in part II of this article, please email me and I will answer at steinfelder@thedilettante.org – or comment on this post].The Baseline Test: My Initial Surprise

I could not believe the results of this test.

For nearly four years, I had been eating what I knew at the time to be the healthiest possible diet – lots of veggies, lean, organic / grass-fed meats, organic, free-range eggs, nuts, seeds, berries, and very limited, but high quality, whole-grains, beans and dairy. And I was pretty damn strict about this thing – frequently known to be the guy who was going to order the quinoa salad at the local sports bar (dressing on the side, please). One time, as I revealed above, I brought my own Tupperware-packed organic grilled chicken breast and steamed veggies to a Super Bowl party. The following year, I was not invited back.

So you might imagine my surprise when, after receiving my results for the baseline test for my Vegan Experiment, I was staring at a total cholesterol number of 213! 213?! I’m the healthiest damn person I know, I said to myself. How could my cholesterol be merely average in the US, (or even a bit above average in this JAMA study)? The US? A country where heart disease is the number one killer? WTF?!

Now, this level may to you (and your doctor) sound OK. OK so you’re not at risk – you’re right around average. Well, average is a reflection of the sample size. Who are we average for? If you are average intelligence at, say, Haarrvarrdd – that means one thing. Ben Afleck and Good Will would still expect you to be writing equations on local pub walls. This is likely going to be different from the average intelligence level, say, of The Center For Children Who Can’t Read Good and Wanna Learn to Do Other Stuff Good Too. Not that there’s anything wrong with this…. So if you are average cholesterol levels – a risk factor for heart disease – in a country in which, on average, you will die of heart disease – is that good? Feels like a low bar, no?

Now, this level may to you (and your doctor) sound OK. OK so you’re not at risk – you’re right around average. Well, average is a reflection of the sample size. Who are we average for? If you are average intelligence at, say, Haarrvarrdd – that means one thing. Ben Afleck and Good Will would still expect you to be writing equations on local pub walls. This is likely going to be different from the average intelligence level, say, of The Center For Children Who Can’t Read Good and Wanna Learn to Do Other Stuff Good Too. Not that there’s anything wrong with this…. So if you are average cholesterol levels – a risk factor for heart disease – in a country in which, on average, you will die of heart disease – is that good? Feels like a low bar, no?

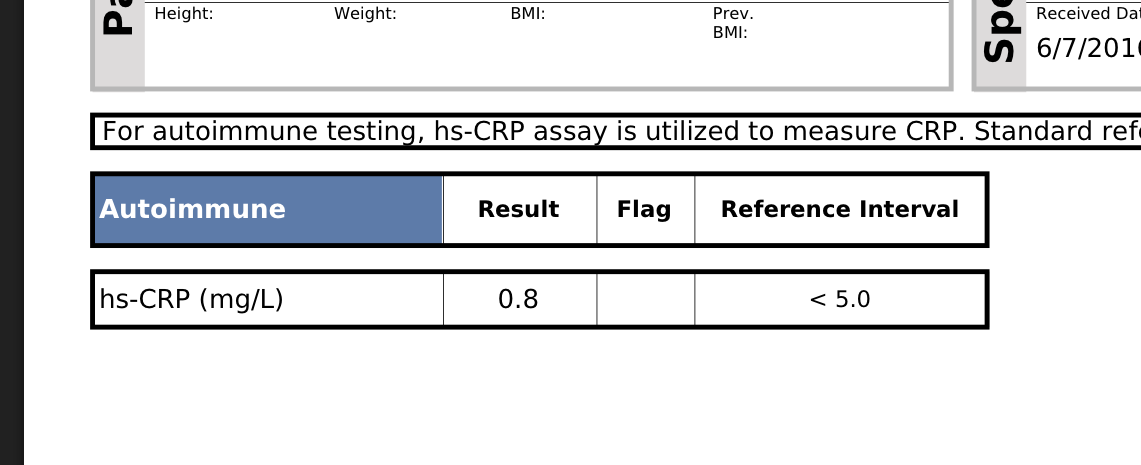

As you can see on my tests, even with what I considered to be a very healthy, very strict, Paleo hybrid-ish like diet – I was struggling in a couple areas – specifically in my lipid profile. Still a couple other areas (Tricglycerides, HDL and CRP – a measure of inflammation) were “good,” but not great; not optimal – which is the goal.

My thinking was simple – and this is the crux of my reasoning for this over-the-top-sounding experiment: there are many things we cannot control – a plane crash, say. But, we can control what we put in our bodies. And if the research convinces us that what we consistently put in our bodies directly influences our systems – heart, blood, and brain – and our systems allow us to be the humans we want to be, then it is probably worth it to do ourselves the kindness of a healthy diet. At least, that’s my take.

So starting from this — I embarked on my one year Vegan Experiment in search of better blood. Would I get it? Would I get excommunicated from my various meat-eating groups of friends and restaurants? Would I become a man-boobie-having, estrogen-doping, ideological, oh-i-don’t-eat-that-i’m-a-vegan saying, I’m-morally superior-to-you implying, muscle-less, pansy-bastard?

Find out the results, next time on… AMERICAN VEGAN!!!

[Part II: The Results]

Justy, out.

Besos.

4 Comments on “Freak To Geek: My Vegan Experiment”

What a great article!! You got it correct about inflammation. Most chronic diseases are inflammation in different places in our bodies!! Believe me, I know. We have to come up with a good diet for the momzy!

Can’t wait to read Part 2!

Cliff hanger!

Love you❤️

Mom(Barrrrrb)

Thanks, momzy! Good diet for Barb on the way.

Loved reading about Shay. Best month overall.

Thanks, Gran. I enjoyed writing about him!