Reading time ~ 9 minutes

Paradox Summary:

We have a clear, clinically-proven way to not only reduce widespread disease, depression, anxiety, but also to proactively improve the daily and long-term function of our brains, hearts and blood. This treatment is often free, can be very enjoyable, and most of its side effects are positive. In fact, in an industry plagued with charlatans, misleading promises, and legitimate disagreement amongst experts, there seems to be consensus on at least one thing: move frequently.

And yet, the Centers for Disease Control estimates that 80% of US adults aren’t meeting the minimum physical activity recommendations of aerobic and muscular exercise.

Why?

I‘ll explore over the next few weeks.

“Move, because your body was made to move. Move, because you will be less likely to die prematurely. Move, because you will be less likely to succumb to any major chronic disease, and more likely to recover from, or thrive despite, any you already have. Move, because it is vital to health. And strive for health not because I say so- but because healthy people have more fun.” Dr. David L. Katz, Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center

Negative Conditioning

A few months back, my buddy, Fred, and I were discussing the topic of “conditioning” over warm bowls of vegan pad thai . (We’re so L.A.). Standing 6’4” with a boyish smile and irresistible charm, Fred is the kind of guy who takes over a room. And as a lifetime athlete and MVP wedding dancer, Fred is no stranger to movement.

Fred, expecting his first child, was telling me that he’d been on a strict eating and exercise plan— and, to his surprise, he had been loving it. Fred was amazed at the difference in his perspective towards exercise these days versus, say, when he played organized sports.

“Growing up, I thought of exercise almost like a punishment,” Fred said. “Something we’d have to do if we goofed off at basketball practice or something my doctor told me I should do. I hated it. But now, I see it as basically the opposite. Almost like a reward. But not like a basic, easy reward— not like eating candy or something. It’s much more powerful.”

When I asked Fred what brought about this change, he paused. “I’m not exactly sure. You know, with my son coming and everything, my priorities changed. I knew I had to be at my best for him. And all I know is that when I get in some sort of workout and eat some green shit, I’m better that day— mentally, emotionally, across the board. And I want to be that for my son. I mean, don’t we all?”

Our Warped Perspectives

IF YOUR CHILDHOOD was anything like Fred’s, your attitude towards “exercise” or “running” had a uchh-god-I-gotta-do-that-now?! vibe. There was an implied feeling that exercise is something we should do or, worse, must do. Something that the authority figures advised, thus ensuring our resistance.

The whole scene reminds me of Orwell’s Winston Smith, fighting through the “Physical Jerks”— the morning movements barked by the telescreen in the classic novel, 1984. Experiencing the scene with Winston, shuddering, we can feel the pain of the calisthenics in the cold, early morning.

The whole scene reminds me of Orwell’s Winston Smith, fighting through the “Physical Jerks”— the morning movements barked by the telescreen in the classic novel, 1984. Experiencing the scene with Winston, shuddering, we can feel the pain of the calisthenics in the cold, early morning.

Where I grew up, there were few telescreens, but there were barking sports coaches. Having to run a mile, or do sprints or suicides, or take a lap were all either punishments for screwing up, or just the part of practice I hated. After being commanded to run a lap, we’d resistantly trudge through it, stomping our feet like a defiant teenager commanded to clean her room.

On my high school lacrosse team, one horrible Tuesday, we were so awful that Coach T just made us run the entire two-hour practice. From then on, Coach T wielded Black Tuesday (as it became known) as an ongoing threat to compliance.

That’s why when I got into high school, I was baffled by those kids on the cross-country team. Umm, your entire sport is based on the #1 sports punishment. “Are you mental?!”

In other words, we were, literally, negatively conditioned. The human brain, psychologists tell us, is highly associative. When something is linked to a bad or good experience, especially one that conjures emotion or requires great effort or pain, that tends to stick.

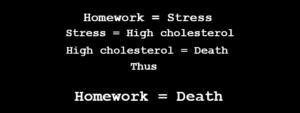

funnyjunk.com

It’s not a tough equation: If you screw up—> you run + screwing up is bad = Running is bad. It’s the god-damn transitive property, for Christ’s sake.

Changing Our Frame

What were the things that I did look forward to in football practice? Or in elementary school? Or at the beach? Or in the front yard of my childhood home, legs bent, hands up in “ready position” while my brother hit low-line-driven tennis balls at me with his 9-iron?

Playing.

I looked forward to Capture the Flag, and scrimmaging, and dodgeball, and running routes, having a catch, and yes, diving for knock-down-9-iron-ed tennis balls. I even loved climbing that absurdly unsafe rope, while, as comedian Gary Gulman jokes, my “safety net” was a 1-inch thick blue mat 50 feet below.

Now, in any of those games, how much running did you do? How many miles? Usually, several.

I despised the “mile run” but then would probably cover double that in just one Capture the Flag game. Black Tuesday was hell on earth, but we all looked forward to the Fridays when we scrimmaged most of the practice, breathing just as heavy at its conclusion. A pro footballer may cover 5-7 miles over the course of a 90 minute game. But how many of them would be thrilled to run “laps”— let alone a quarter-marathon?

What’s my point? There are two points:

Point #1: Exercise = Play

Exercise, like so many health-related activities, may be merely a matter of Mindset. To gain much of the benefit of moving and dramatically increase the percentage of those that get those benefits, we can dump “exercise” and simply play a sport, the drums, hit a swing-dance sesh, tend to the garden, or take a long and lovely walk.

Think of the difference between “going to ride bikes with my friends” and “getting on the exercise bike for 30 minutes.” The former, we think of as Positive Conditioning; the latter— a the Seventh Circle of Hell. What’s more fun—- an after school trail-ride with your friends or a 45-minute sesh on a Peloton bike, staring into a screen?

But, although this perspective shift would be huge, it does not seem to be our biggest problem…

Point #2: We Exercise For the “Wrong” Reasons

Even if we do exercise, whether from a change in perspective or not, we tend to exercise for the wrong reasons.

Most of us exercise (present company included) in order to acquire shiny things trim waistlines and nice calves. We vaguely understand that health is good, but if we are honest, we are trying to look good and feel good first, and sometimes, that holds even when we may or may not actually be good (i.e in our blood, brain and hearts).

But it turns out that ab and bicep benefits, while effective as finite, short-term goals, repeatedly fail to motivate us long-term. And, even when they have been effective motivators, they seem to come with negative consequences.

For example, Traci Mann has been studying diet and exercise out of the “Eating Lab” at the university of Minnesota for decades. Mann tells us that focusing on weight loss would be the “wrong” reason to eat healthy and move a lot. Wrong meaning ineffective. The “right” reasons center more around biological and psychological health. And, paradoxically, these “right” reasons may more dependably lead to the abs and buns we sought after in the first place.

You might be thinking: But why does it matter if we exercise for the “wrong reasons,” as long as we are doing the damn thing? Is it not good enough that we’ve gotten ourselves to prance like a damn gazelle on this electrical trainer 4 days a week? Now we need the perfect reasons too?!

Unfortunately, yes, it does seem that way. Motivation matters, especially the type.

What Drives Us?

“When the reward is the activity itself–deepening learning, delighting customers, doing one’s best–there are no shortcuts.” Dan Pink, Drive

In his book, Drive, author Daniel Pink summarizes the current research on motivation in the areas of behavioral science and psychology. Pink’s research shows that there are two types of motivation — extrinsic and intrinsic.

Extrinsic motivation is something driven from without: a million dollars, shredded abs, fear of being fired, peanut M&Ms. These are all extrinsic because they come from a source external— the “carrot and stick” model of motivation. They can be compelling in spurts, but seem to eventually hit a threshold, after which, they lose their shine.

After a while, being paid more for a job you don’t enjoy in and of itself will not increase your motivation. This is why entrepreneurs leave high-paying banking and law jobs for a cup-o-noodle diet and a dream.

Conversely, Intrinsic motivation comes from within: purpose, personal interest, joy. The reasons are manifested on your own. You go and read to toddlers on Friday afternoons not because those little bastards pay well, but because children and their education is important to you.

Now, capitalists and body-builders, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying we should all work for free or hate biceps. Money is cool and curls, of course, get the girls.

External motivations can have a powerful impact— but only to a point. Just like increase in salary for that high-paid banker, the image of a great bod will hit a wall. It is easier to sustain in the short-term. But short-term success is no indication of long-term sustainability. Eventually, we see diminishing returns.

But even worse than diminishing motivation, focusing on merely external benefits can actually diminish the performance itself. That is, not just your drive to get to the gym, but the amount of burpees you complete after you arrive.

Pink shares several reviewed and replicated studies where paying people to complete a task that they were previously doing out of enjoyment of the task itself, decreased, for example, their creativity and persistence on a given project. Extrinsic rewards have also been shown to reduce the propulsion of long-term goals and “morally engaged activities.”

So what sort of motivation does lead to long-term sustainability? What are the “right” reasons to exercise?

That is what I’ll explore in Part 2: The ‘Real’ Reasons To Exercise

Besos,

Justy

One Comment on “The Exercise Paradox, Part 1”

JP,

Love the article(of course, I’m the mommy)! But, also, what you said was so true. Exercise was always thought as a punishment growing up. And when I grew up(a long long tome ago), the girls never did much in gym class but exercise their mouths! And in college, thank goodness I had to walk to class! I didn’t even know where the gym was! Wow!

Can’t wait til the next article.

Got to go! Time to exercise!

Love you,

The Mommy