Around September 2013, I stopped eating breakfast. It was a sad time.

Since forever, I’d been one of those I’m-starving-as-soon-as-I-wake up-so-don’t-talk-to-me-until-I-have-my-eggs, kind of breakfast eaters. I also was a staunch believer in the axiom that “breakfast is the most important meal of the day.”1. All that to say–throwing out breakfast was a change I did not take lightly.

What could possibly lead to someone to give up a thing as pleasurable as breakfast?

The book was called Engineering the Alpha, 2.0— a book by a celebrity trainer and fitness writer on how to transform your body. Now, as bro-ish as the title makes this sound– and it is—amidst the cursing and the shirtless, tanned pics of jacked dudes, it also had some surprisingly science-based information on something I’d been hearing a lot about at the time: Intermittent Fasting (“IF”). As we saw in part 1, fasting has been around for thousands of years, but certain versions of IF are an advent of the last couple decades.

So what is IF?

IF is actually an umbrella term that holds a lot of variations. The basic definition is that you refrain from eating during defined intervals of time. This can mean fasting for an entire day a couple times per week—e.g. the “5 and 2” diet, where you eat whatever for 5 days per week and fast 2. Or it can mean fasting within a window of time on a daily basis.

The latter form— fasting in a defined window of time on a daily basis— that goes by another name: Time-Restricted Feeding (“TRF”)2. TRF is the a form of IF that Engineering the Alpha, 2.0 (“ETA2“) advised, and it is the subject of my 2020 fasting experiment below. Well, except with one significant change via some brand new fasting science– I’ll get to that in a second.

But before I get to the experiment and results, you’ll need to know what TRF is and why researchers have been so excited about it for the last decade.

TRF— the basics.

Prior to that fateful Fall of ’13, my “eating window” ran from approximately 8am to 10pm (14 hours). After reading ETA2, I changed it to 12 PM to 8PM (8 hours) to accord with the book’s protocol. And begrudgingly, I bid ado to breakfast.

What’s this “eating window” I speak of? At first sight, it might seem a foreign concept. But, if you think about it, you’ll realize that there’s actually nothing new about an eating window. In fact, you already have one.

If you’re like most Americans, you probably begin eating each day around 7 AM (eggs, cereal) and stop eating around 10PM (cookies, chocolate ice cream). Surprise: that’s an eating window— a 15-hour eating window. What TRF seeks to do is to (a) shrink that window and (b) potentially migrate it to a different part of the day.

The ideal form of TRF, the authors claimed, was to begin eating in the afternoon— e.g. something like 1pm-9pm— and fasting until the following day at 1PM again. They tended to start at 2PM and go to 10PM. But in any case, they were pretty dead-set on skipping breakfast.

What did they have against breakfast?

For one thing, they claimed that the only research claiming that “breakfast was the most important meal” showed only association with healthy habits. In other words, there was no proof that eating breakfast actually caused health. It merely showed that people who tend to be healthy, also tend to eat breakfast. And they cited evidence to that effect.

But it was more than that. It wasn’t just that skipping breakfast was neutral— but that it might be beneficial. To support that position, they provided several small rat and human (mildly convincing) studies (and another). But in any case, their primary conclusion was not about breakfast at all. It was about timing. They were saying—it doesn’t matter what time you eat. What matters is for how much time you eat in a given day. In other words, the size of your eating window. Thus, TRF.

And, no wonder— the purported benefits of TRF were outrageous. TRF would deliver everything from fat-loss to metabolic improvement to insulin sensitivity, to longevity— all while maintaining or even bolstering muscle gain. A veritable wonder drug.

Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t 100% sold. Given the proposed benefits, TRF had the distinct character of a too-good-to-be-true panacea. The exact thing you’d find in a diet book right after the section on life-saving superfoods. And, indeed, like the Yellow Light foods, the science seemed divided.

However, I also didn’t see much of a downside in giving it a shot. This would be an experiment. And just like My Vegan Experiment or Project Veggie Muscles, the idea is to try, monitor closely, report, and adjust over time.

And so I practiced the ETA2 version of breakfast-free TRF for about 5-6 years. Skipping breakfast was hard at first. But, over time, you tend to adapt. After a month or so, when I woke up, I was no longer hungry. My body was no longer expecting food, perhaps.

After a few months, I started to love this new way of eating. I found that restricting my eating to a window was not only easy, but I preferred it. I found my mind clearer in the morning before eating, and cutting off at night, approximately two hours before bed, helped my sleep. I also found that I ate slightly less throughout the day, unintentionally. There’s just so much you can fit into that 8 hours.

I did this right up until 2019, when I came across some recent TRF research that had been piling up out of a well-known lab in Southern California. As Keynes apparently once said, “when the facts change, I change my mind.”

And so, I changed my mind on breakfast, again, and on an apparently better way to do TRF.

New TRF Science: the eating window and our circadian rhythm

In 2017, Dr. Satchin Panda, a researcher out of the Salk Institute of Biological Studies, reported on research that was polarizing. On the one hand, it reinforced the strength of the TRF research I already knew. But, on the other hand, it changed everything.

The change came in two parts. The first part was the theoretical basis for TRF— the justification for why we should eat in a concentrated window on a daily basis. The second part was about the practical application— in other words, how do we incorporate TRF into our diet, and what are the “best practices.” Dr. Panda’s research advised a new specific time that was best for that window.

First, on the scientific justification for TRE. Previously, the research had just been about the benefits of efficiency. If you focus eating all in one concentrated time per day, the body will be freed from the demanding job of digestion and reallocate energy to the million other processes operating in the background (breathing, thinking, balance). Additionally, this time free of food would allow for more cleansing of the body. As one researcher put it: IF allows “cells to perform their ‘housekeeping’ better, clearing out waste particles more efficiently.”3

This was still likely true. But there’s something even more interesting— the relationship between eating and our biological clocks. The “biological clock” that is run by our “circadian rhythm” (CR).

Your CR is the clock by which your body operates. It more or less tracks the rising and setting of the sun. In the morning, we rise with the sun, and the processes that wake up the body and get it ready for alertness, movement, and consumption are all begun. 4. Among these morning processes are the release of a load of hormones and chemicals that ready the body for food digestion. Conversely, at night, a different set of chemicals are released that tell the body to take focus away from alertness and digestion, and focus more on sleep, processing information, storing memories.

Dr. Panda advised, as had been theorized prior and corroborated since, that eating should abide by this clock. In other words, you should try to consolidate all eating to the window of time in which the the sun is in the sky. To eat before 7am or after 6pm would be to go against the body’s processes. For example, once the sun goes down, the darkness cues the body to produce melatonin. You know melatonin as the hormone that tells your body to get sleepy. But it also tells the body, e.g., to stop paying attention to digestive practices and start focusing on, e.g. memory consolidation.

Let’s say you live in New York City. In the December, the sun rises around 7AM, and sets around 6 PM. Therefore, all of your eating should be done between those times— an 11 hour window. Dr. Panda advises that in no instance should you eat outside of a 12 hour window, but that you may benefit even more by shrinking that window. So, say, eating between 12pm and 6pm (6 hours) might provide more benefit than just with the sunrise and sunset.

So that’s the theoretical basis that was changed— the adding in of the understanding of our CR and how it impacts when we should eat, in general. Simply put: eat while the sun is up. Pretty simple.

But that’s a 12 hour window. What if we want to get the larger benefits of the smaller, 6-9 hour window? Is there a better part of the day in which to concentrate that window?

Dr. Panda has an answer to that, and it is the basis for my 2020 Intermittent Fasting Experiment.

Bringin’ Breakfast Back

Recall that, from 2013-2019, I was practicing IF, but using the afternoon / evening eating window from 12-7pm. I was skipping breakfast, which I had learned was not to be thought of as a sacred cow. Well, like the nutrition version of JT, Dr. Panda was bringin’ breakfast back.

But for different reasons than initially supposed.

The old reason for making sure to eat breakfast was based on things like “starting your metabolism” or “it keeps you full more of the day.” There appears to be limited science to the first concept, more to the second (provided you’re eating whole-plant, fiber-rich foods), but neither of them are as powerful as what Dr. Panda and colleagues showed.

What Dr. Panda showed was that because of our CR, and the differences of morning and evening body chemistry, that the same exact meal eaten in the morning would be less calorically costly. In other words, if you eat 500 calories— say, a large oatmeal with fruit, nuts, seeds, and cashew milk— at 7am on Day 1, and then eat that same exact oatmeal at 7PM on Day 2, Day 2 would be worse for your waistline. Due to our circadian rhythms, the same calories are worse handled at night than morning.

The takeaway: an early eating window is better than a late one. Engineering the Alpha told me to skip breakfast. But it seems I might be better off skipping dinner.

With the science early and somewhat divided, I didn’t quite know where to move. As far as I was concerned, this put IF in a sort of “Yellow Light” scenario. Just like Project Veggie Muscles or My Meat Experiment or my water-only fasting experiment —when there exists disagreement or uncertainty among experts, the only way to figure it out fast is to test it out and measure the results.

Enter— my Intermittent Fasting Experiment.

My Intermittent Fasting Experiment: Ground Rules and Goals

So in 2019, I decided to continue with TRF, but to change it in accordance with Dr. Panda’s findings, and with my CR. That is, I went back to breakfast (hallelujah) and gave up something else. A little thing known as dinner.

Dinner Like a Pauper

Is skipping dinner crazy?

My answer: not any more so than skipping breakfast. Dinner is just a title we use for “last meal of the day,” and, according the The Atlantic, it really wasn’t a big thing until post WWII. In this case, I was just moving dinner earlier in the day– albeit, three to four hours earlier than the average American family.5

With Dr. Panda’s findings being so compelling, I figured that I had to give this a shot. And because of my bachelor style lack of responsibility for anyone other than myself, I would be able to practice extremely early TRF, perhaps leading to more dramatic results. That was the theory anyway. But did it work?

Let’s get to the ground rules.

The Rules:

I’ve been experimenting with my diet for about 15 years.

I’ve done the low-carb, no-carb, slow-carb— if it had the word “carb” it it, you can bet your sweet ass I’ve tired it. I’ve also tried everything from 6 meals a day to zero meals for a week, and everything in between. When I was in college, a friend of mine named Harris, who knew about this habit, would invariably ask me: “So, what new diet you on now?”

One thing I’ve learned through all that experimentation is the need for slack.

Slack is an allowance for error, permission to slip a day or so per week. Because of other obligations and desires—- work, travel, family, dating— I knew 100% compliance was out of the question. I mean, I’m a bachelor, not a monk. So I decided that around 80-90% compliance would get me where I needed to be.

The following were the rules I settled on:

(1) The Window. For an entire year, I would eat only between the hours of 9am and 5pm, with special effort to condense that to a 6 hour window from 10am to 4pm (allowing for ~15% slack). However, in no circumstance should I eat outside of a 12 hour window. Practically, that means if I am planning on going out to dinner with friends or a date, and I hypothetically will be out until 10PM or after, I won’t begin eating that day until 12 hours prior to that projection.

(2) The Diet. I would eat a Green-Light dominant diet such as the one I was on for My Vegan Experiment or Project Veggie Muscles. And it’s basically the diet I eat 90% – 95% of my life with little to no struggle. 6. Specifically, eat as much as I want of the following foods: veggies, fruit, nuts, seeds, whole grains, legumes. If I wanted to eat 10 bananas and a jar of natural peanut butter— so be it.

- Additionally, as always, very little Red Light foods (sugar, processed grains or snacks, alcohol), and a few yellow here and there (wheat, soy, saturated fat).

- The key to diet here: As much food as I want. No calorie limit whatsoever. TRE is not about limiting what you eat, its about limiting when you eat.

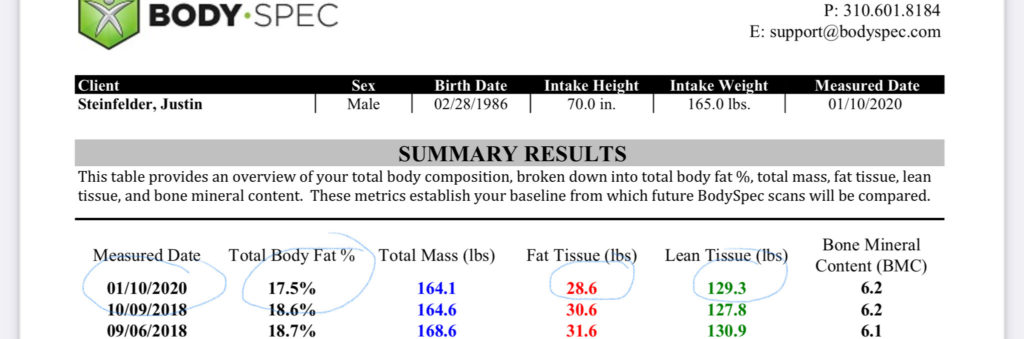

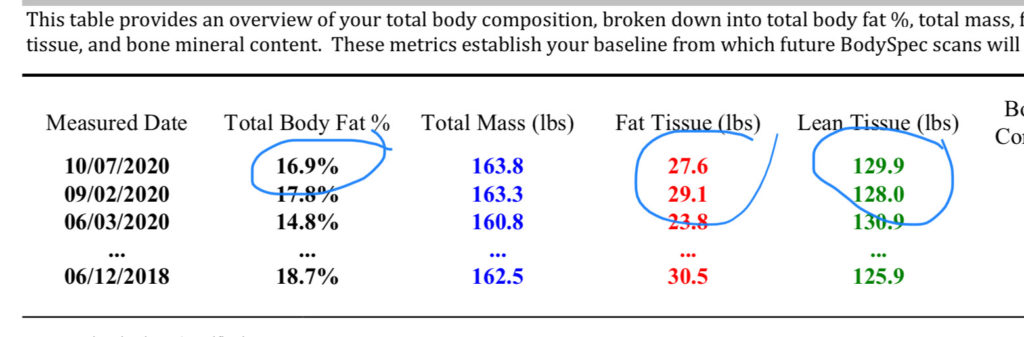

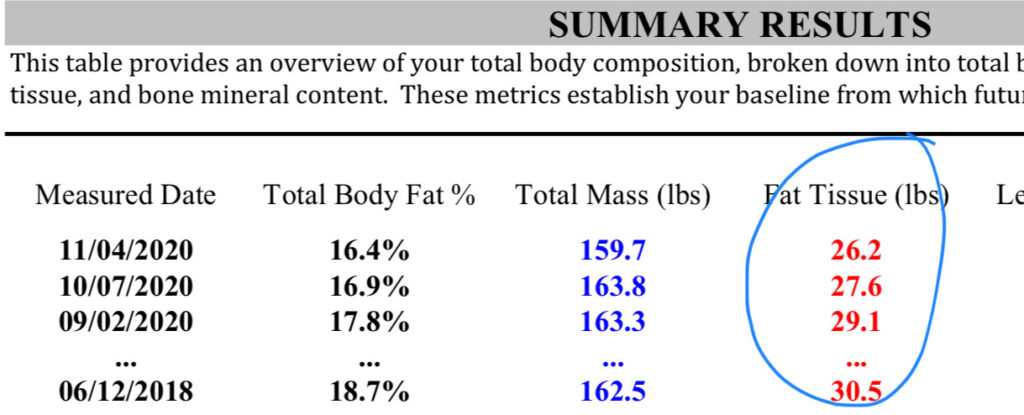

(3) The Measurements. Every 6 weeks or so, I would get a DEXA x-ray scan to monitor progress. The frequency of monitoring has a two-fold advantage. First, I can seee if I a moving in the right direction. And second, if I am not, and that is do to a lower than 80% compliance, it will motivate me to get back in the window. “What get’s measured, gets managed.” As I’ve done in the past, I used a DEXA scan at BodySpec to get the body composition measurements. Is the DEXA scan 100% accurate? It doesn’t appear so. But it’s pretty good. The important thing, however, is not the measuring device in absolute terms, but keeping the measuring device consistent.

I’ll give you an idea of instrument variability for body composition tests. Around the same time in 2018, I got measured by calipers (the clips that grab fat at various points on your body), DEXA and a newer method called bioelectrical impedance within a weeks of each other. The body calipers said 15.7%, the DEXA 18.7%, and the BIA was 14.3%. The bottom line, it doesn’t matter. We are looking for relative improvement, not absolute totals.

(4) The Goal . I am making one single change— moving my eating window back about 3-4 hours. Changing this one variable, allows, as well as one person can, to run an effective experiment. The overarching goal is to see if one tiny tactic can alter my body composition significantly. My initial specific (or “SMART”) goal is to drop 4% body fat by 12/31/20.

So what happened? Did it work?

The results were remarkable as much for their successes as their failures. It turned out that I actually ended up with two experiments in 2020, unintentionally.

The first experiment was the one I just laid out— eating in a very small and early-day window from about 10am-4pm daily. And that lasted through the first five and a half months of the year. But then in mid-June, and again in July-August, I headed to the east coast to be with family (brother got married), and I relaxed the eating window mightily.

I’ll take you through those rollercoaster like results now, and finish with the end of the year return to greatness.

The Results, Part 1: January – June

The Baseline + 6-Week Check In

So I began in January, eating between the times of about 9am – 5pm. Again, that’s all I changed. I didn’t limit my eating— I was eating the same foods I always eat and a similar number of calories on a daily basis, only earlier.

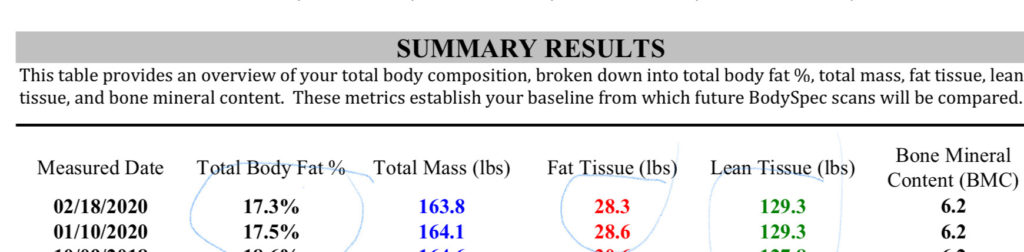

I did that for nearly 6 weeks, and checked on my progress.

Ok, Not overwhelming, but not nothing.

There was reason to believe something might be changing, but I wasn’t completely convinced. Thats’ because weight can fluctuate. Maybe I was working out slightly more or happened to be eating slightly less. Maybe the machine made a small error. I was only at 20% of the goal and half way through the quarter, I’d need things to start kicking in.

Because of COVID, I couldn’t get a test again until June. But, man, it was worth the wait…

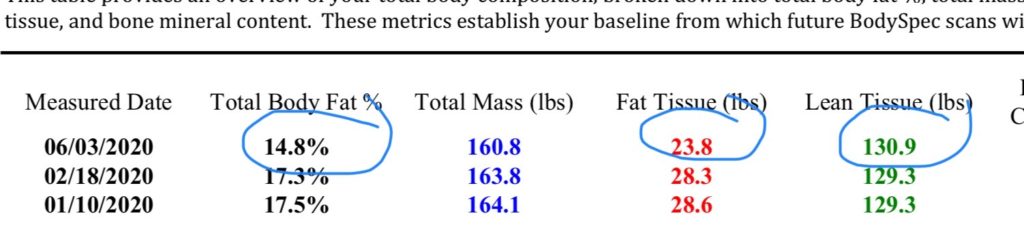

The June Test – 5 Months In

Hello.

At less than halfway through the year, I was more than halfway to my goal. Almost 3% body fat drop in just 5 months? That’s unheard of with this simple of a change— merely moving dinner a few hours earlier.

Recall, I wasn’t limiting calories. I also didn’t change the contents of what I was eating, nor did I impose any major change to physical activity.7

And notice, the lean muscle mass. There, what we are looking for is at least for it to hold. But here, it actually went up. Which means even though I was “skipping dinner”— I could still build muscle.

You might be wondering what my body looked like. Well, I don’t have a picture for you from this experiment, given that really isn’t the point of this article. However, to give you some perspective on the absolute fat percentages here— below is a picture from my Veggie Muscles experiment from Summer 2018.

Though I put on 5 lbs of muscle between these two pictures, my body fat percentage for both was 18.7% bf according the DEXA. As you can see, there’s some fat on there, but by no means am I chunky. More like a beefcake. Well, more like a Beyond beefcake.

So imagine (if you can do so without losing it) a lentil powerhouse like that, only stronger, and 4% less body fat, which is what I was above in my June test, five months after beginning this TRF experiment. I think I speak for all of you when I say: hubba hubba, you sexy, veggie muscle man.

But that was in June. Then, summer came, and everything fell apart….

A Midsumer’s Undoing

Ok, it was only June and I was already more than halfway to my goal. I’m feeling good. But then, a terrible thing happened—summer came, and I lost it.

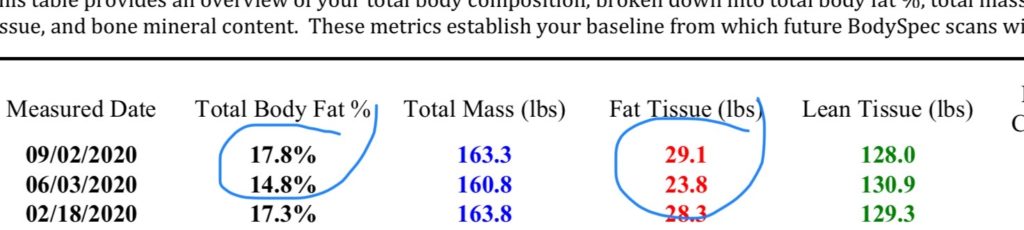

I spent nearly all of the summer with my family on the east coast, beginning in mid-June (for my brother’s wedding), with a small break in between, and the second trip ending in late August. Over the course of that time, the percentages flipped. 80% of that time, I ate dinner until between 7p – 9p, like most of the free world. That effectively wiped out the experiment over that time period.

I expected a regression, naturally. But I didn’t expect it to the extent that a September results showed…

Can you believe that?!

I mean, 10 weeks with these dinner-eating bozos and I am right back to chunksville.

But, what this seemed to do, unintentionally, is create a more effective experiment. Because I’ve now gone from late eating window, to early eating window, back to late. Essentially, I’ve shown the relationship in both directions. That if you eat earlier, you’ll lose fat. If you eat later, you could gain it.

Now for the final touch. With only a few months until the end of the year would I at least be able to get back on the track to where I was?

I felt pretty good about my chances.

BOOM! Crazy. Right back down, half way to the June mark. Not bad for only two months back on the grind.

Conclusion

So what can we conclude from this experiment? Did I hit the goal?

Well, sadly, I don’t know.

At the beginning of November, I took a cross-country trip back to the east coast, and then down to Florida to see my family. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a place to get a DEXA scan. And anyway, we were going through the worst of the pandemic, as you know. So, we don’t know for sure. But I think we can draw some conclusions.

Considering my own results coupled with Dr. Panda and others, one thing we can say is that, at the very least, the early eating window is worth testing more. That’s not to say it’s definitely the real deal. Indeed, reviews of the science as recent as 2017, and even 2019 are still inconclusive.

But, still, it seems to me worth experimenting with.

If you wanted to try it, what would you do? Well, obviously not everyone is going to be able to stop eating at 4pm. I mean, that’s insane. But there are ways to introduce it. For me, to whatever extent possible, I am going to adopt the following rules:

Rule #1: Never eat longer than a 12 hour eating window. The results from most of the IF studies, whether early or late, is that you do not want to eat outside of a 12 hour window in a given day. It’s not only body fat, it’s inflammation, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity— the whole nine yards. It’s also very manageable. 8a-8p or 7a – 7p. Not that hard.

Rule #2: Eat Dinner as early as possible. Whatever your breakfast time, to whatever extent possible, eat dinner earlier. Not only is this helpful for digestive and blood health, but I found that it improved my sleep. I was much more comfortable going to bed when I wasn’t full. I’m personally going to keep a 10-6 eating window, and earlier dinner when I can. Dr. Michael Greger, in his book, How Not to Diet, advises finishing all eating prior to 7PM. That seems very doable.

Rule #3: Test it a couple times per year. You don’t want to adopt a new way of eating without measuring the results. Unless you’re intent on simply assuming everything went to plan. The bathroom scale is not enough, b/c it doesn’t tell you body composition. If you’re just losing a bunch of muscle or water weight, you’re not actually getting healthier.

And there she is. 2020 experiment in the books. Let me know if you end up testing TRF yourself. I’d be curious in the results.

Any requests for 2021? Email me at steinfelder@thedilettante.org or leave a comment below.

As always, thanks for reading.

Besos,

Justy

- This was largely based on an uninformed understanding of what breakfast impacts the body. More on this below

- In other contexts, especially in less scientific contexts, TRF is alternatively called, “Time- Restricted Eating,” which has a better ring to it for humans (as opposed to rats). I go with TRF simply out of habit (and because I’m want to feel sciency).

- A process known in the biz by the name of cell autophagy (“auto” = self; “phagy” = to eat).

- This process is managed by what is called the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain

- Apparently this later dinner ~7pm or so, has migrated north by two hours since the 1950s. Given my findings below, that could be some of the cause for the health issues in the US.

- meaning I’m not on a “diet” — this is just the way I prefer to eat.

- I say no “major” change b/c, unintentionally, it did turn out that I walked about a mile more per day this year. That might be anywhere from 50-80 extra cals per day. But as you’ll see, that can’t be enough to explain this effect.