Reading time: About 11 minutes – or about the average amount of time a typical office worker gets prior to being interrupted at work.

“My greatest skill was being teachable,” said Michael Jordan, believed by many to be the best athlete of all time. “I was like a sponge. Even if I thought my coaches were wrong, I tried to listen and learn something.”

And it wasn’t just Jordan who thought this – his coaches marveled at this fact according to Roland Lazenby, author of, Michael Jordan: The Life, the most comprehensive bio on MJ of which I am aware.

“To his coaches his capacity to be coached was his single most impressive attribute, beyond even the eighteen-year-old’s spectacular physical gifts,” writes Lazenby. And then quoting Jordan’s Hall of Fame college coach, Dean Smith: “I had never seen a player listen so closely to what the coaches said and then go and do it.”

From CEOs to authors to athletes, there seems to be no question about it – the ability to constantly and consistently receive and learn from feedback from others appears to be vital to growth and success in any field. I don’t think I’m stating anything revolutionary here.

However, if we are honest with ourselves, at least at one time or another, we sometimes struggle with taking criticism from others. At least I know I have – mightily so.

When I was growing up, I consistently got defensive about certain kinds of criticism from certain kinds of people. Here and there, this may have happened on the athletic field. But, more times than not, the times when I really struggled was criticism of any kind, constructive or not, were those that seemed to challenge my intelligence.

This uber-defensiveness in the arena of academia, or even simply trying to “be right” in an argument, was perhaps due to my self-diagnosed ailment of “fixed-mindedness.” This is not some made up affliction, but one that world-renowned, Stanford psychologist, Carol Dweck, has studied for decades.

Dwecks research, the subject of which runs the gamut from school children to famed CEOs to world-class athletes and coaches, has revealed two types of personalities: the growth and fixed mindsets.

A fixed mindset, for instance, suggests a person that views talent or intelligence as something innate. Something that cannot be developed much after your early youth.

Dweck’s research suggests that people who believe intelligence is fixed tend to view criticism as an indictment of their character and identity rather than helpful or constructive. As a result, these people tend to reactively shield themselves from its contents and potential benefits.

Contrast that with those people who consistently viewed intelligence and “talent” as something that could be learned and forever developed. For this group, feedback did not beget a defensive reaction – it provided enthusiasm to learn and energy to improve.

These findings have been corroborated in neuroimaging studies of the brain. For those with the fixed mindset, brain imaging showed a deactivation of the neocortex – the part of the brain crucial for higher learning, and an activation of the amygdala – a major fear-processing and fight-or-flight brain region.

As you may predict, the opposite was shown in the brains of growth-minded participants. The neocortex seemed to actually be stimulated by criticism.

For me, a lot of Dweck’s research rings true. And it could also provide justification for the typical disparity in my reaction to feedback on the athletic field versus the scholastic arena (which I pointed out in this review of Outliers).

In athletics, I knew I had to get better, and, more importantly, I believed I could. Conversely, I believed that things like IQ were largely fixed, and, as a result, I tended to view IQ as part of my identity. A challenge to it would, therefore, be a personal attack.

But now, years later, perhaps a fraction less hardheaded than I was in my earlier years, I have noticed a slow but certain improvement in this arena.

This progress has been accelerated in recent years by people like Dweck and longitudinal research suggesting that personality traits often change throughout one’s life. These findings have, fortunately, cast a massive doubt on that depressing old dictum that confidently declared: “people don’t change.”

But, even knowing this, I still struggle at times with certain forms of feedback in circumstances that I find extremely difficult to improve upon. Like, say, when I believe the person giving feedback is in no position to be giving it. “Are you kidding me,” I might mumble to myself, “who is he to be criticizing me on this!!!!”

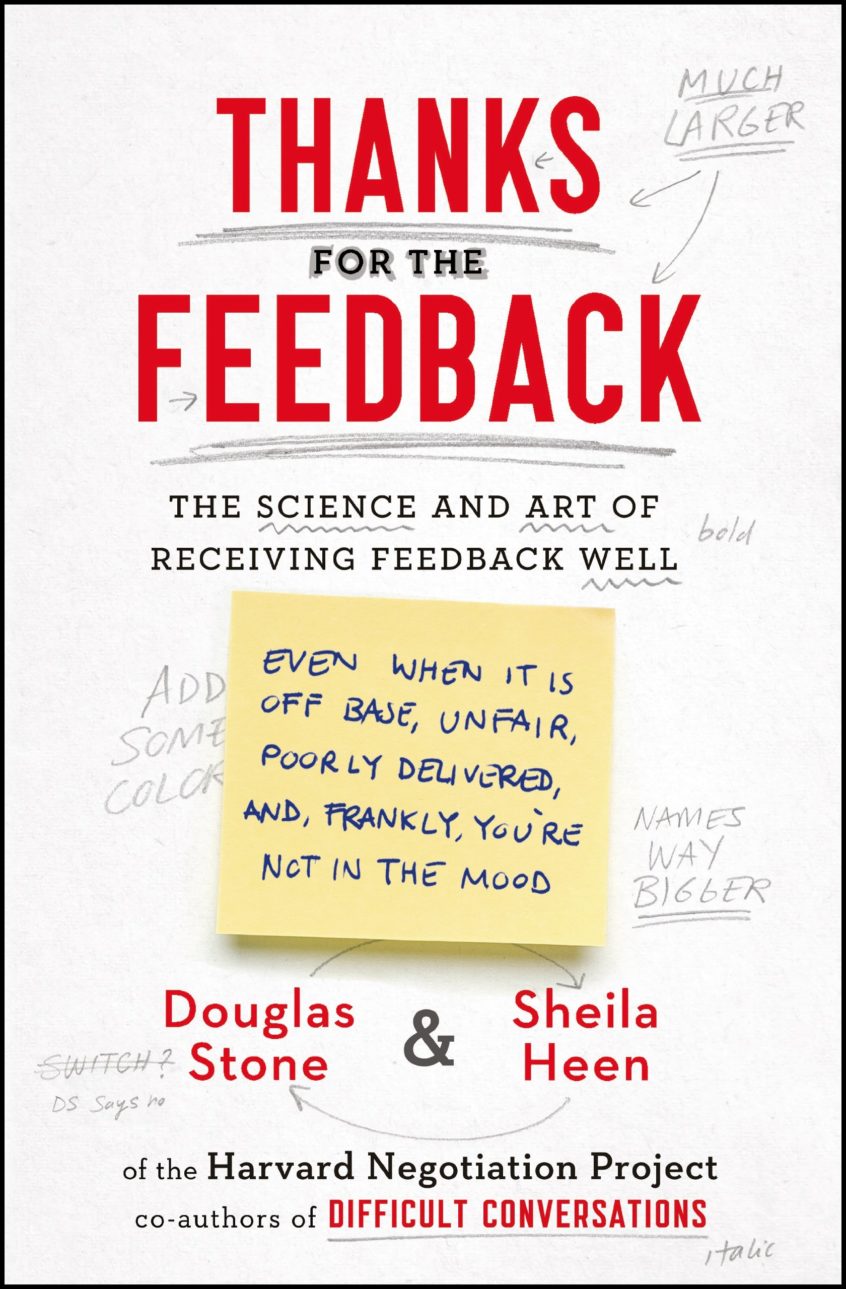

Knowing this has been a problem, and believing I must force myself into seeking out better alternatives or risk stagnation, I sought out sources that could provide some insight. I took on the un-fun task of reading Thanks For The Feedback, a book by a couple of Harvard Law professors, Doug Stone and Sheila Heen, that I would typically avoid like ze’ plague.

The book uses scientific research to reveal the best strategies for giving and receiving feedback productively. I am going to spare you the experimental citations in this little blurb, but I will tell you the things I found practically helpful in my own life.

The following is what I found useful.

Thanks For The Feedback

The premise of this book is one to which I have alluded above. The authors call it “creating pull.”

“Creating pull is about mastering the skills required to drive our own learning; it’s about how to recognize and manage our resistance, how to engage in feedback conversations with confidence and curiosity, and even when the feedback seems wrong, how to find insight that might help us grow. It’s also about how to stand up for who we are and how we see the world, and ask for what we need. It’s about how to learn from feedback—yes, even when it is off base, unfair, poorly delivered, and frankly, you’re not in the mood.”

Not so novel a concept, right? We all probably realize this on some level.

However, there were at least three scenarios discussed by the authors which revealed tactics that I have since taken and tested in my own life. As a result, I have seen dramatically different responses – both in my own mood and temperament, and that of my collaborators, teachers, and bosses.

Identify Your Triggers

In the book, they talk about three different scenarios that commonly occur and keep us from benefitting from feedback, or, as the authors say, prevent us from “engaging in skillful conversation.” The three triggers are:

- Truth. You feel that the criticism is factually incorrect, and, as such, your reaction is more likely to be a bit more indignant.

- Relationship. This is where you don’t feel the person who is giving the feedback holds a status in the subject matter such that they deserve to give you this feedback. This happens regardless of whether or not the criticism is correct – something that may cause you to miss an opportunity to improve. This is obviously not ideal.

- Identity. This is where something about the criticism gives you that raging feeling in your stomach – something has stuck a nerve. The feedback, whether true, or from a person who is in a perfect position to call it out, is at risk of being mishandled due to your embarrassment, ego, fear, or whatever.

Just by giving things a label – a scaffold or lattice work, as master-investor, Charlie Munger, calls it – we are able to become aware when our reactive mind may be distorting the data. I have noticed significant improvement just by hearing some feedback, feeling the feeling in my stomach, acknowledging it, and then trying to assess the situation with that tiny bit of space created.

For example, I most recently experienced this via emailed criticism from my boss. I had an issue with the truth of it – and there was possibly a bit of my own identity feeling defensive. But, given my knowledge of this tendency, I was able to catch this reaction, take a few minutes to gather myself, extract the value in the criticism, and respond thoughtfully. A major win.

Avoid “Switch-tracking”

Switch-tracking is a phenomenon that I know all too well – it is forsaking the “what” of the feedback – that is, the content being offered – and, instead, concentrating on the “who” – that is, the giver of the feedback. We do this for three primary reasons. The authors explain:

“We can disqualify the giver on any number of grounds—the most common involving trust, credibility, and the (lack of) skill or judgment with which they deliver their feedback. And once we disqualify the giver, we reject the substance of the feedback without a second thought. Based on the who, we discard the what.”

Do you recognize this? I do.

Scene: I do something, someone points it out, even rightly, but they do it in front of my boss, say, and so I barely even realize the truth of it and instead switch the conversation, at least in my mind to: “why would you do that in front of him?! You always do that. You have no tact!” As a result, neither of us improves.

Or how about when someone who you view as horrible at something criticizes you for being horrible at it. Even if it is accurate, I think to myself: “wait a second, you are criticizing me for being late? Have you ever been on time? Are you kidding me?! You never listen to me when I point out how you’re late.”

I’ve switch-tracked here – I’ve turned their argument – you should be more timely – to my ad hoc attack – you never listen to what I tell you – or my credibility argument – my mistaken view that because they are late, they cannot identity when others are.

How to avoid this: (1) identify (2) Understand (3) “signpost”

We’ve spoken about the importance of identifying. That is always key.

But we have to make sure we understand exactly what the problem is. Sometimes, it is hard to tell, and we assume we know the problem but we are wrong – perhaps due to the “often-clumsy way givers raise their concerns.”

So tell them what you think their grievance is – confirm it with them. Then “signpost.”

Signposting is pointing out the two different grievances and addressing them both in turn. First, it’s probably a good idea to acknowledge their issue as important, and addressing it first. But then, make sure you cover your concern saying: “id also like to come back to a separate issue I have afterwards.”

I’ve tried this as well, also in the context of work, with a colleague. It was extremely helpful and we both felt better about the situation after. In fact, she pointed out how appreciative she was of how I handled the situation.

Dismantle Distortions

“One of the biggest blocks to receiving feedback well is that we exaggerate it. Fueled by emotion, our story about what the feedback says grows so large and so damning that we are overwhelmed by it. Learning is the least of our worries; we’re just trying to survive.”

Again, I can easily link past experiences to this diagnosis. It often isn’t the thing said or the person who says it, but my reaction to it – the feeling building in my head and in the pit of my stomach – that increases the impact of a relatively minor inconvenience to sometimes blinding heights.

What to do?

- Prepare. In his best-selling book, Smarter, Faster, Better, researcher Charles Duhigg discusses how successful people create “mental models” in their heads. That is, they continually simulate in their mind conversations they are about to have in order to prepare for how they might tactfully react if this or that is said. Hall of Fame coach, Bill Walsh, echoed this in his autobiography calling it “contingency planning.” Either way – this strategy has been shown effective in multiple areas.

- Step back, Reassess. Identify what is being said, what is not being said, and attempt to disentangle the raw content from the emotional story your mind is creating. This few minutes of reflection will, just by dint of the exercise itself, provide the space to recalibrate back to your baseline mood.

- Empathize. This is hard. But if you can create that few seconds of space, try and think to yourself: “how would I see this situation if I was this person.” This allows you to do something called “steel-manning” – a term to describe when you look at someones argument in the most favorable light possible. As if they are the gods of this subject matter and flawless in personality.

Ok, that’s it.

I know this article hasn’t been fun to read – but hopefully you’ve viewed it as I have – as a very useful and necessary exercise.

I know that given my ghastly historical record of taking criticism, you may be tempted to disregard what I’ve written above – but try not to “switchtrack” and again – remember these three things:

- Identify Your Triggers. Become aware of how you tend to react poorly to feedback – be it truth, relationship, or identity based. Merely becoming aware will give you the space to respond thoughtfully.

- Avoid the Switchtrack. Don’t confuse the content of the message with your view of the messenger, or their tact. Identify, understand, and “sign-post.”

- Dismantle Distortions. Don’t allow elevated emotion to create a harmful story in your head. Simulate conversations, take a step back when you’re in the moment, and try to look at it from their perspective.

Feedback is crucial for improvement overtime as we are often blind to our repeated mistakes. Other people can help, but they sometimes are not so skillful at the criticism and we are often not prepared to take it. Listen to the feedback, or, better yet, seek it out.

Doing so may put us in a better position to take the famous advice from Bruce Lee:

“Absorb what is useful, Reject what is useless. Add what is essentially your own.”

Enter the dragon, young grasshopper.

Thanks (in advance) for the feedback. 🙂

Besos,

Justin

2 Comments on “Being Thankful For This Is Vital For Improvement, Experts Say”

Thanks for the feedback!!

Enjoyed this very much. I will try to use the three pronged attack when getting defensive towards criticism. BC I AM DEFENSIVE!