The most crushing defeat happened to my Baltimore Ravens against the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 2011 NFL playoffs.

In sports, losing sucks, but it sucks even more when you think you’re going to win. When you should have won. You were up the entire game, but then something happened, it started slipping away, and what was once a huge lead becomes a stinging loss. That’s how it happened for the Ravens on that January night in Pittsburgh.

The game started off great. We were the underdogs in a notoriously brutal rivalry, but we came in the building and just exploded. We were up 21-7 at the half, in full control. The stadium was silent.

But then, it all turned on us. We fumbled the ball in our own territory, the Steelers picked it up, scored on the next play. 21-14. The next possession, Flacco threw an interception at our own 25. The Steelers capitalized— it was 21-21. Every Ravens fan watching experienced the same feeling: uh oh.

Hypothetically, we were fine. There was still plenty of time in the game, the score was tied. But it didn’t feel like we were tied. We all knew where this was going. We seemed to have lost something.

“A lot of game left here,” Chris Collinsworth said. “But I think the Ravens lost their momentum.”

He was right, we never recovered. We lost 31-24. It was a rough night.

*

When we think of momentum in sports, we think of what the Ravens lost. A string of events that carries an opposing force. A “changing of the winds,” a “shifting of the tides.”

But when you really think about it— what exactly does any of that mean?

Was there actually a force that shifted sides, or was Collinsworth just using a very loose metaphor that doesn’t translate? And even more to the point: does it matter? So what if momentum is more metaphor than material? Is there a downside?

I’ll argue that there is a downside. That in hard pursuits— winning a Super Bowl, building a business, overhauling your health— there is no such thing as momentum. And that relying on it leads to failure.

But I’ll also argue that there’s a better way. That instead of using an analogy, you should call the thing what it is. What is actually changing here?

Does a startup “gain momentum,” or does it manufacture several small wins in a row, increasing trust in the market, gaining confidence in itself? Is it momentum you’ve built writing those first three scenes of a pilot, or have you just started to prove to yourself that you can write three more?

This will all become clear to you in a minute. But, before I can convince you to ditch momentum, it will help to understand what momentum actually is.

What is Momentum?

Ok, let’s be clear— in the world of physics, there is such a thing as momentum. Stand down techies and engineers, you need not berate me on Reddit. My point is that it’s not what most people think. It’s much simpler.

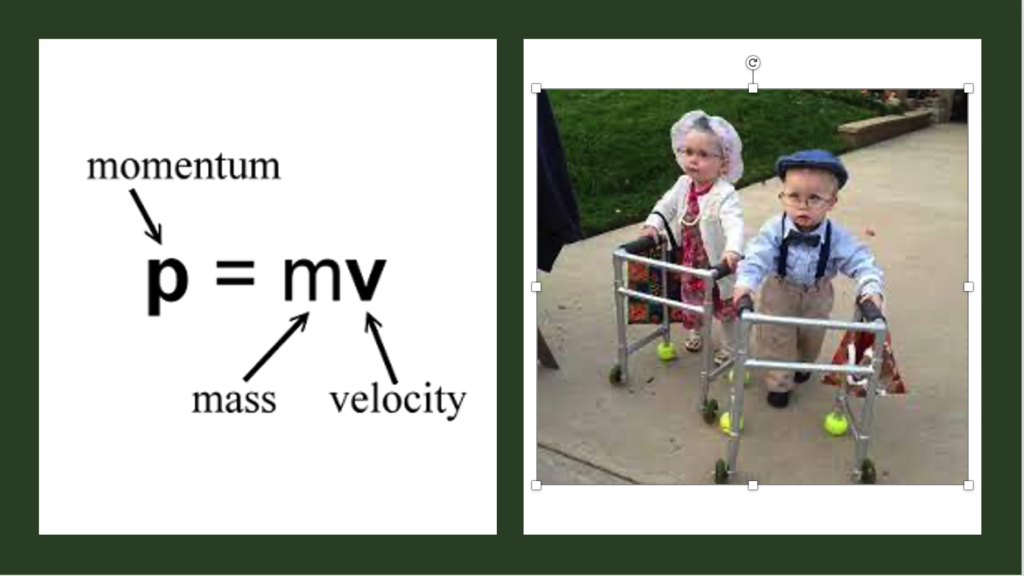

Here’s the definition: “the quantity of motion of a moving body.” Or mathematically, mass multiplied by velocity—essentially weight times speed. In other words, anything that is moving at all has momentum. Anything. “It’s no more than how much stuff is moving and how fast that stuff is moving,” one professor said. Any thing, any speed.

A car doing 75 has it and so does a downhill-rolling ball of snow. So does an oil tanker, a spiraling football, even your grandma, trudging along with one of those four-pronged walker, tennis balls on each leg.

So, literally speaking, the Ravens had momentum. But then so did the guy getting his popcorn and the referee, and the little orange flags on the tops of the goalposts.

But Collinsworth meant something else. Something illusory.

What Do We Really Mean by Momentum?

Collinsworth didn’t mean momentum literally. That the Ravens were once in motion, and then stopped moving. Everyone was still physically moving and made of material.

He meant it as a metaphor. That the Ravens were figuratively moving in the right direction. Things were going well, until they weren’t.

I have no issue with using momentum as a metaphor, except for one thing– the implication we draw.

That there is some movement outside of the players. Some outside, accompanying force, that makes their play easier. The idea that when you put together the good plays, the rise in confidence and swagger, the other team’s fall in hope, that these elements combine to make some other thing. A thing that it carries some of the load. That takes some of the burden out of what is hard.

But does that really happen?

Hold that thought. Let me try to explain this in another very popular, but equally troubling way. It’s called “Escape Velocity.”

The Misleading Idea of Escape Velocity

Ask some startup guru in Silicon Valley for advice, and they may tell you that the most important thing you can do is to simply get started.

To ‘don’t just stand there, do something.’ To ‘Ready. Fire. Aim.’ To, as LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman likes to say, ‘first jump off a cliff, then build your plane on the way down.’

Recently, an analogy to space travel has become popular. That like a rocket ship attempting to orbit the earth, what you need to generate is “escape velocity.” The speed necessary to escape the earth’s atmosphere.

“Did you know that a rocket burns 80% of its fuel just getting to orbit?” They’ll start. “Most of the energy, therefore, is burned in starting the journey to the moon. In gaining enough velocity to escape earth’s gravitational pull.”

This, they will tell you, is just like any hard pursuit. The most energy is spent in the beginning— generating enough force to escape the grip of gravity. After that, you’ll float like you’ve been drinking Willy Wonka’s fizzy lifting drink.

In other words, your project— a business, a painting, a diet— is the rocket ship. Spend enough energy in your launch, and you’ll need much less energy to keep going. Just begin and then you get all these reinforcements— habit, momentum. Then you can drop your launch engine and cruise, the pale, blue dot in your rear view.

Here’s the problem: while this may be correct for space, it’s only half right for earth.

Yes, you need to start. You need to escape from ground zero. And that’s certainly harder than say, eating Cheetos on a lawn chair. But is it the hardest part? Not even close.

When you’re ‘taking off,’ you have the ground to push off of. Like a sprinter off the blocks, or the swimmer diving into the pool, there is energy inherent in the start. Starting is sort of fun, it’s new, there’s a spark.

But once you ‘escape’ the start, you’re now in a new environment. And often this environment is much more ambiguous, much bigger. It’s like you’re a boat who has left the dock, but you’re miles and miles from your destination. At some point, the land behind you disappears and only horizon in front of you. You’re just out there alone, on the open sea. You have only your compass, the wind, your hope, and your head.

What you need in that ‘messy middle‘ as Scott Belsky calls it— the open sea, the middle of a 10,000 meter race—it’s not the velocity of a launch. It’s the slow progression of persistence. You’re out of the frying pan, and into a much larger, longer, slower fire. And most people burn out.

Here’s the truth: starting is easy. It’s staying that’s difficult. Or as a one writer put it:

“Enthusiasm is common, endurance is rare.”[1]

Everyone Starts; Nobody Stays: Changing Your Diet

Let’s take an example from your own life using a subject I write about a lot: diet.

Think of your inner circle of people: family, friends, colleagues, local baristas, whatever. Now estimate how many of them have started a diet. I’ve just taken 20 people at random from my phone contacts. The amount I know for a fact have started a diet is well over 80%. And that’s just the ones I’m sure about.

Almost everyone you know has been on a diet. Not only that, they probably lost weight. Maybe they did the Whole30, maybe they stopped eating burger buns, maybe they only ate burger buns, but they did something. They probably even lasted for a few months, maybe even a year.

If they did this— diet, maybe spin class, some decent sleep— for an entire year, they must have built some good momentum. Surely, a year is sufficient to reach escape velocity, isn’t it? But are they in orbit? Or back on the ground, eating full burgers once again?

Let’s think about it from the other side. How many people do you know that have overhauled their diet and changed their body (and probably their life), and were still going two or five years later? If they reflect the research, it’s a very, very low number. (And that’s just the people that actually completed the study).

Two facts on diet. First, regardless of type of diet, almost everyone that goes on one (which is almost everyone you know) tends to lose weight—initially. Second, over half of those people will gain all of that weight back, and give up the diet, after 12 months. After two or ten years? There’s not that many studies, but Dr. Tracy Mann at the University of Minnesota estimates between 5% – 15%.

Everyone starts, nobody stays.

Here’s the thing, all of the momentum in the world isn’t enough to escape the gravitational force of cakes and pies. Dieters launch, they fly, but they come crashing back to earth—usually, to the couch. As Bad Blake sang, “It’s funny how fallin feels like flyin for a little while”.

It’s the same in any hard project. Whether it’s a startup, you want to be a rockstar, or your training to be a professional golfer. Everyone starts.

I was interested in golf for a half a second. One summer, I went to the range almost everyday. Momentum machine, folks. But at the end of the summer, with momentum hypothetically at its height, I stopped. Back to school.

My brother, on the other hand, was also there everyday that summer. And then for everyday in fall and winter. And then every season in the decade that followed. He went when he was tired, he went to practice his short game, he hit balls in the snow. I started, he stayed.

The result: he’s a scratch golfer, I duck-hook brand new ProV1s into the woods.[2]

You Are Not A Snowball; You’re Sisyphus

Many hear momentum and think that rolling ball of snow.

It starts down the hill, it gains size and speed, until it rolls itself into an unstoppable force. The snowball, like an avalanche, would keep moving without anyone pushing it (provided it was still on the hill), just because it had been moving before.

But you won’t. There’s no one pushing. You’re not on a hill. There’s no outside force. There’s just you.

Actually, it’s the other way around. As you go, it gets harder. If anything, the hill steepens, the climb gets harder, more people drop off. Many join at the start—that’s where enthusiasm lives. But few will be there at the end, where you need something different: endurance.

You are not a snowball. You’re Sisyphus, rolling your bolder uphill. But just like Camus’ version—you must picture him smiling. Happy in doing the hard, consistent work, day in, and day out.

Because while momentum is made up, there are other things you can actually grab onto.

One is called belief.

Ditch Momentum, Gain Belief.

It may sound juvenile, even naïve, but Rocky is one of my heroes. Yes, I mean Rocky Balboa, the fictional boxer.

I learned a lot of lessons from watching those movies. Ones that I still hold today. Each movie had something— the two against Apollo, Mr T, Tommy Gun, Michael B Jordan, even Thunderlips. But it was in Rocky IV that he taught me what might be the most enduring lesson.

It was about the power of belief.

*

Ivan Drago was a monster boxer from Russia.

He towered over Rocky. He punched 4-5 times harder than the average professional boxer. He was on steroids, almost superhuman, indestructible. As his trainer told the press, “whatever he hits, he destroys.”

He didn’t mean that figuratively. He killed Apollo— Rocky’s mentor, coach, and friend. Beat him to death in an exhibition fight. After that happened, Rocky agreed to fight him—in Moscow.

Fast forward to the fight. Rocky is in shape, looks great. He trained as hard as he’s ever trained for this fight. He is scared, we find out, but he’s ready.

The fight doesn’t start well. He comes out in Round 1 and just gets crushed. He’s cut and bloody, his eyes are swollen, he gets knocked down several times. His wife, Adrian, puts her head in her hands as if to say, “I can’t watch. Please let him survive.”

The bell rings. He survives, but barely.

Round 2 starts off like it’s going to be the same thing. Drago knocks him down several times. Rocky tries to counter, takes big swings and totally misses. At one point, Rocky tries to ‘tie up’ Drago, but the Russian picks Rocky up and throws him across the ring. It looks like this round might be the end.

But then, a ray of light. Rocky, looking as if this is his last-ditch attempt, ducks a punch, and swings again at Drago, only this time he connects. And not just connects, he hits him hard. So hard that he cuts Drago. A huge cut under his left eye.

“HE’S CUT, HE’S CUT” yells the announcer. “The Russian is stunned.”

We see Drago stagger. He checks his eye with his glove, see’s the blood, and is in disbelief. A moment of uncertainty falls over his face, as Rocky proceeds to go after him.

Rocky wins the second half of that round, landing punch after punch. But the crescendo of the scene comes out after the round, when Rocky is in his corner. It’s what his trainer says, and it’s what we all want to hear.

“Ok, You got him hurt bad,” his trainer says. “Now he’s worried. YOU CUT HIM! YOU HURT HIM! YOU SEE, YOU SEE, HE’S NOT A MACHINE. HE’S A MAN.”

Drago’s corner is the opposite. “He’s not human,” Drago says. “He’s like a piece of iron.”

*

It’s a Rocky movie, so we all knew Rocky was going to win. But it wasn’t until that moment, after seeing that he could hurt the imposing Russian, that Rocky knew it too. Something real did change after that cut— it’s true. But it wasn’t winds or tides or momentum. It was belief.

The fight ends up going 15 rounds, Drago losing some, but Rocky losing most. It didn’t get easier after the cut, it got harder.

What happened after the cut, was that Rocky proved something to himself. That if he hung in there and kept to the plan, even when his ribs ached and his jaw was broken, if he kept coming out of his corner, kept getting up after being knocked down, then, maybe, he could really do it. He could win.

It wouldn’t’ be velocity that led to the win, but resolve. Not momentum, but mindset. He’s not a machine, Rocky saw, he’s a man, just like me.

And it’s the belief in that possibility that makes a difference.

*

Look, belief, just like launching, doesn’t make things easier.

Love him or hate him, but one thing that is absolutely clear about Elon Musk– he believes in what he’s doing. But as you can see here, belief helps persistence, but it doesn’t make it easier. At least not the round to round, day-in, day-out. You still have to show up and show up and show up—for decades.

Hard things don’t get easier. They probably get harder. But you can change their meaning. You can change your perspective. Your confidence. Your mindset. Call it small wins, call it the motivational force of progress. But don’t call it momentum.

Call it what it is: belief.

*

“It’s not how hard you hit,” Rocky told his son, “it’s about how hard you can get hit, and keep moving forward.”

When you do get hit — and you will— don’t expect momentum to pick you up. It won’t. Momentum doesn’t deal well with opposing forces.

Those require something else.

[1] From Professor Angela Duckworth in her book, Grit (which I’ve written about here.)

[2] Sorry, dad

[3] Ya, I didn’t say spoiler alert because (a) that phrase makes me want to puke and (b) there’s a 30 year statute of limitations. The movie was made in 1985. Get a life.

One Comment on “There’s No Such Thing As Momentum (But There’s This)”

Loved this one. Belief was key. I think that it’s so true! If you believe in yourself, nothing can get in your way! I should use this for my Mantra!

Love you,

Mom