1. It’s Not The Size of Your Willpower, It’s How You Use it

Self-control is, like, 50% funny and 50% sad.

We sit in front of a plate of cookies and we just cannot stop ourselves. Cannot do it. The smell of gooey dough and dark chocolate commands our brain: must eat all cookies; must eat now. Watching someone else go through this is the funny part. Regretting our riotous cookie-attack— that’s where the tears come in.

How is this self-insurrection possible? I mean, we’re us—we’re reasonable human beings. It’s our choice, isn’t it?

Usually, when we can’t control things, there is a good reason. They are outside of our influence, and it’s not our place. The decisions your boss makes at work, policies in the government, or the outlandish comments your uncle makes every Thanksgiving. You can say your part, advertise your stance on the matter, but it’s usually useless. Uncle Bob is going to say what Uncle Bob is going to say.

But, if there is one place where we are in the perfect position to exercise complete control then it’s over our own. You want to exercise control and you’re in position to do so. And yet, your level of discipline, particularly in the moment, lies somewhere between toil and hopelessness.

Don’t worry, you’re not alone. Sure, I may appear disciplined, writing a book about diet and behavior, and all. But sit me in front of a plastic barrel of peanut butter-filled pretzels, and I’m no more discipline than a labradoodle. At minimum, half of that tub will vanish by night’s end— of that much you can be sure. And, it’s not just us, it’s most people. ‘Lack of willpower’ is consistently cited as the #1 reason people don’t accomplish their health goals[1]. (And the reason empty PB pretzel tubs across the globe).

But here’s the thing— you probably don’t have a willpower problem. Not in the way you think.

It might seem like more willpower is what you need, but based on the years I’ve spent researching and experimenting with diet and self-control, that’s the wrong diagnosis. Though there exists some controversy in the willpower world[2], all sides acknowledge the following: it is not the case, as it’s commonly believed, that you either have it or you don’t. Self-control is less about having more, and more about what you do with what you have. More how than how much. Just like other parts of your body (theoretically), it’s not really about how big your willpower is, it’s how you use it.

The first step to using your willpower more effectively is understanding how it works. In a minute, we’ll cover the three surprising truths about the mighty Self-Controlled. But first, it’ll help to recall just what this self-control battle looks like inside your brain.

2. The Two Ways Your Brain Makes Decisions: The Elephant and The Rider

Let’s start with what we know.

Your brain has two modes of making decisions— two modes of thinking. It’s pretty complex, so it’s helpful to think of them as characters. Enter: the Elephant and the Rider.

One mode is impetuous, reactive, and drags you to the plate of cookies. It’s the part of the brain that leads to road rage and binge eating. That’s the ‘Elephant.’ The other mode is the opposite: reasonable, cool, and collected. It thinks about your long-term goals, and aspires to your best-self. It invests in your 401K instead of a Land Rover, and goes to therapy instead of screaming into pillows. It’s the ‘you’ sitting on top of the Elephant. Meet the ‘Rider.’[3]

The Elephant is the enemy of self-control. The Rider is the savior. Willpower, then, is getting the Elephant to comply with the Rider’s goals. The problem, however, as anyone who has ever narfed down a pint of Rocky Road in three minutes flat knows, is that the Elephant is quite a strong fella. And its pretty impatient with Rider instruction.

So how to control the Elephant?

Well, that might be the wrong question. If you take a look at those Marine-like freaks who test highest in self-control, you would probably get the sense, as most experts have, that it’s not really a process of control, per se. They tend to use other strategies and techniques that only look like control. Fortunately, those techniques are learnable, however counterintuitive.

The first step is observing how those Willpowered machines tend to operate. And, crucially, how they do not.

3. Three Surprising Facts About People With High Willpower

(i) The Willpower Paradox

The first thing that’s surprising about those with high willpower: they don’t use a lot of it.[4]

Remember Steven Seagal movies? Seagal would fight 10 random dudes, they would be out of breath, on the ground, and bleeding. Meanwhile, Seagal would need only to fix his (extra small) tank top. He’s the best fighter, but not because of superior strength, but due to technique.

The Willpowered fight the Elephant like this. They are like martial artists. Like Seagal, they don’t necessarily have more strength. They use the strength they do have in ways that produce the greatest effect, but— and this is crucial— with the least strain.

In self-control science, this is sometimes known as the ‘Willpower Paradox.’ The paradox is that those with the most ‘power’ use it the least. But, it turns out, this isn’t a paradox at all. There’s a simple explanation.

They appear discipline not in spite of this sparing use, but because of it. Like Segal, they conserve their willpower for times with most impact. “People who are good at self-control … seem to be structuring their lives in a way to avoid having to make a self-control decision in the first place,” said psychologist Brian Galla. In other words, they conserve their powers.

But when do they actually use their control? That leads to the second important fact about those with high willpower— they use leverage.

(ii) High Willpower Is High Leverage

The second thing to understand about the Self-Controlled, is that they use their restraint in particular circumstances. In areas where they get a lot of bang for their buck. I call these ‘high leverage’ areas.

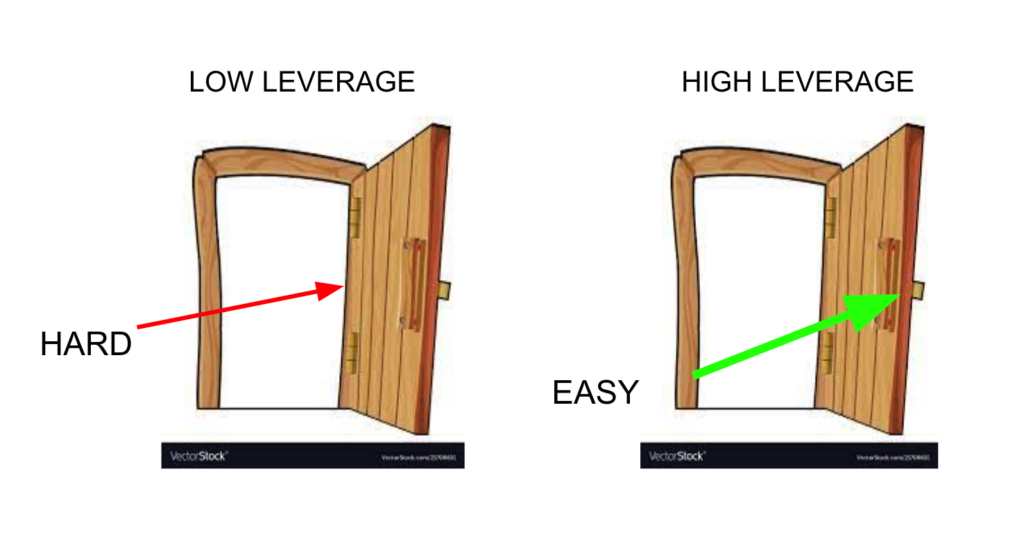

Think of a door. Have you ever tried to close a door by applying pressure near the hinges? You’ll notice this takes more strength to move the door than if you push it near the knob. That’s because the entire door itself is a lever. When you push near to the hinge, you’re eliminating the help of the lever, and so moving the door is effortful. But stand further away from the hinge— i.e. at the knob—and it becomes easy. You’re using leverage.

A lever is all about substituting distance for power. Instead of standing right near the thing you want to move (or change or avoid), stand further away, and use a ‘lever’ to move it. What you’ll find is that, like closing the door from the knob, the effort required decreases proportional to the length of that lever. “Give me a lever long enough,” Archimedes said, “and I shall move the world.”[5]

For those seeking diet control, here’s the point to remember: the Willpowered act from a distance. They don’t use their self-control to avoid eating a cheese pizza sizzling right front of their faces— that’s insane. That’s like trying to close a door from the hinges. Low-leverage madness.

The Self-Controlled, conversely, use their willpower before the pizzeria— that’s the high-leverage time. They use that distance to either avoid the pizza shop altogether, or as cool, thinking time to create some kind of what-to-do-when-pizza-is-in-my-front-of-my-face, back-up plan.

Having said that, there’s probably going to come a time when you show up at the pizzeria without a willpower plan. Some call that, ‘living your life,’ or, you know, ‘not being a complete psycho.’

At this point, the Willpowered have one last trick in their well-organized, tote bags. When they’re in the moment, staring at that seductive, sour-dough margherita, they turn to an old friend from the East: awareness.

Ohmmmmm.

(iii) Awareness Creates Control

Leverage is all good and well, but occasionally, you’ll be staring down the barrel of a sizzling pizza slice. So what to do then? There’s one thing that the Self-Controlled do in the moment that seems so simple, there’s no way it can possibly work—but it does. The ability to pause.

One of the key factors that allows the Elephant to rule the Rider, especially in the moment, is brute strength. It’s the same thing you’ll notice if you try to speak on a stage in front of 100 people, or, ask someone out for the first time. There is some sort of instinctual resistance to it. A strong pull in the other direction.

But—and here’s the good news— there’s a subtle weakness to this brute strength. And it may be the simplest bit of wisdom that those Disciplined puritans ever discovered: the Elephant’s strength is temporary. If you can remember, in the moment, to pause, take a breath, look directly at the Elephant’s trunk, maybe even giggle at yourself, that reactive, ravenous power starts to fade.

__

“If there’s a secret for greater self-control,” writes Stanford lecturers Kelly McGonigal, “the science points to one thing: the power of paying attention.”

Strange as it seems, one of the greatest weapons of the highly discipline, is not their burly self-control, but a delicate self-awareness. They are more like monks than machines.

And when you’re successful in this simple act—when you start to pay attention, and “recognize,” as McGonigal says, “when you’re making a choice, rather than running on autopilot”— it’s only then that a reassuring feeling might occur to you. The one that the Willpowered know well, and the rest of us long to discover.

That when we start to really pay attention, maybe, just maybe, the Elephant isn’t as strong as we thought.

[1] According to various American Psychological Association surveys. (https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2012/02/willpower)

[2] This controversy mostly surrounds whether Willpower is a finite source, like muscular strength. And whether the amount of Glucose in your brain is that source. (https://hbr.org/2016/11/have-we-been-thinking-about-willpower-the-wrong-way-for-30-years).

[3] I get more detailed on this two-brained system, and how to use it to your advantage on the way to eating a healthier diet, in my ebook, here.

[4] The Elephant and Rider are a creation of psychologist Jon Haidt based on his own derivation from Plato and his horse and rider.

[5] I love how people just drop Archemides like they know anything else about this guy other than this one quote that they probably read off Good Reads. And you know what’s funny? We don’t actually know if he said it. It was only reported by a follower of his. In any event, while I have you, here’s something interesting about the whole lever-moving-the-world thing. How long would the lever actually have to be for a person of average strength to move the world? About (10^23) 1,000,000, 000,000,000,000, 000,000 meters away, or over 8 million light years, which would put Archmedies several galaxies away. That’s one large stick.