Reading Time: ~13 minutes, or about 68% of the time the average American reads per day.

OVER THE PAST COUPLE OF MONTHS, many of my family members and friends, all of whom aware of my blog and my plant diet, urged me to watch a pro-vegan documentary called, The Game Changers. “You haven’t seen it yet? Oh my god, Justin— you’ll love it! We watched it, and now we’re all going vegan!”

The film, produced by James Cameron, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Jackie Chan, sets out to show the supposed overwhelming benefits of an all-plant diet for health and performance, primarily via the story of former UFC Champion and martial arts expert, James Wilks. Wilks, a life-time meat-eater, suffered major knee injuries a few years back and, with his career on the line, set out to research the best method of recovery. Enter: the plant-based diet. Throughout the documentary, The Game Changers, shows how the plant-based diet not only restored Wilks (and a host of other professional athletes) to health, but left him in better shape than ever. Along the way, Wilks, not-so-subtly, condemns meat-eating and describes how “everything he had been taught about protein was a lie.”

Now, as I stated, and as you may have deduced from my many diet-related experiments and plant-forward articles, I’m a herbivore. So, you might think that if these carnivorous friends and family of mine were so emboldened by this movie, that I, well-practiced in the Vegan arts, should feast on this film, gushing with pride and I-told-you-sos, whilst stuffing my face with butterless popcorn.

And yet, while I do love nutritional-yeast-covered popcorn (and who doesn’t?), my reaction was the opposite. I responded that not only had I not seen the movie, but was extremely resistant to it.

Why? Was I merely being an unappreciative contrarian? What’s the real reason I was so resistant to seeing a movie that apparently confirmed all I believed about diet?

Enter: the most famous psychologist you’ve never heard of.

*

When Prophecy Fails: Doubling Down On Our Beliefs

IN THE EARLY 1950s, Dorthy Martin, a Chicago resident previously involved with L Ron Hubbard, organized an association on the basis that she was getting messages from the planet Clarion. That message was that the planet would be destroyed in a great flood on December 21, 1954 at midnight.

The rule of the group was that you couldn’t tell any of the outside world about the oncoming disaster. Additionally, the group was encouraged to defect from commitments of their current life (jobs, churches, families) and double-down commitment to the group. And many (but not all) followed suit, leaving their families and jobs with nothing more than a “I must do this.”

Finally, the group came together for the fateful evening and sat in glorious anticipation for the flood to come. The only issue– the flood never came.

You might expect that the group would quickly disperse after the non-occurrence of the prophecy. And in fact, many of the fringe members of the group — the ones that still remained skeptical— did just that, chalking it up to a loss, and going back to their normal lives.

But, as world-renowned psychologist Leon Festinger describes in the book, When Prophecy Fails, that is not what happened to the people who were more staunch supporters. The members who had left their jobs and families — i.e. put in great investment and believed deeply– ended up redoubling their commitment, going out into the world and heavily proselytizing on the event.

The new claim was that we’d been spared this flood because of the group’s commitment, but that other dangers were lurking in the distance. The association is still intact today.

*

IT IS NATURAL TO READ a story like that and to assume that these people were crazy and that they are nothing like you. But in fact, as well see, that is actually an aspect of what was really infecting them– an aspect of all of us, including you and me. We think to ourselves: “well, they’re crazy. I’m reasonable.” But according to the intensive study that was conducted on the group, we’d be incorrect to think that.

Dr. Leon Festinger, one of the top five most eminent psychologists of the 20th century (just behind Freud and Piaget) diagnosed the group with something he called, “Cognitive Dissonance” and its what gave me pause about The Game Changers.

Cognitive Dissonance and Game Changers

“Much of the time, we use reason, facts and critical analysis not to form our opinions, but to confirm what we already see, feel, or believe.”

Elliot Aronson, The Social Animal

What Festinger postulated in 1957 was that frequently we experience an uncomfortable divide in our minds. The divide comes when we believe or feel one way and then we encounter evidence that contradicts that thinking. Alternatively, it might happen when we hold one belief about ourselves– like “I am a good and reasonable person” and we act in an alternative way– say by smoking after knowing about its direct link to cancer. The theory has been widely corroborated and pushed forward over the last 60 years, in large part by Festinger’s PhD student at Stanford, Elliot Aronson.

Aronson, who was also mentored by famed psychologist, Abraham Maslow, is the only psychologist in history to win all three of the American Psychological Association’s annual awards in research, writing, and teaching. He also wrote the textbook on Social Psychology called, The Social Animal, which Harvard’s Daniel Gilbert has described as “the single best book ever written on social psychology.” In other words, Aronson knows his stuff.

Aronson describes CD thusly:

“Cognitive dissonance results from the clash of two fundamental motives: our striving to be right, which motivates us to pay close attention to what other people are doing and to heed the advice of trustworthy communicators; and our striving to believe we are right (and wise, and decent, and good).” Sometimes, Aronson points out, these two motives are on the same side. But more often, “we seek information and then ignore it if we don’t like what we learn.”

After reading this book, I was on heavily alert for risks of CD in myself.

*

WHEN I WAS BEING PROPOSITIONED to watch Game Changers, it was fear of the impending CD I was going to experience that worried me. Because, as we saw in the Prophecy case above, It isn’t just the ideas that contradict our beliefs that activate its power, it is also the ideas that confirm our beliefs that put as at risk for further entrenchment without the benefit of careful (and factual) consideration.

This aspect of CD is sometimes called “confirmation bias.” And as Aronson says:

“Of all the mind’s biases, the confirmation bias is central to how we see the world and how we process information: we notice, remember, and accept information that confirms what we already believe, and tend to ignore, forget; and reject information that disconfirms what we believe.”

Aronson gives a key example of a less extreme, Prophecy-like case that I find compelling regarding the death penalty.

*

A GROUP OF STANFORD STUDENTS were hand-selected for their stated beliefs either for or against the death penalty’s ability to deter violent crime. The students were then shown two articles, one showing evidence of the effectiveness of the death penalty in deterring crime; the other paper showed compelling evidence that it did not deter crime. So for each student, one paper would confirm and the other would disconfirm their beliefs.

Aronson points out that if the students were rational, they might take a look at the conflicting evidence and decide this problem is complicated. CD, on the other hand, would predict that they try and point out what is wrong with the study against their beliefs, and point out what is obviously correct about the article in support of their preexisting view. And this is exactly what happened.

After reading the evidence, the students on both sides ended up behaving in the same suspicious way. Instead of recognizing the complexity of the situation, the student’s, much like Dorthy Martin’s followers, clung to their preexisting beliefs, singing the praises of confirming evidence and downplaying or discrediting the opposing data.

Further illumination was shown on which arguments they could best recall. If they were rational, Aronson explains, they should recall most effectively the arguments that were most rationally plausible, regardless of belief. But what happened was they remembered best only the plausible arguments that supported their beliefs and the implausible arguments that supported the opposing position.

Just like your overly liberal uncle or republican mother, they remembered best the weak arguments that supported the other side. This enables them to say: “this is the best they have?! See, I told you I was reasonable and good, and they weren’t.”

It’s Not You, It’s Me

PERHAPS THE MOST INSIDIOUS ASPECT of the cognitive biases is that, like the devil, we’ve convinced ourselves that they don’t exist, at least in ourselves. Precisely because of their function to keep us ‘reasonable and good’— we can’t see them. But that’s only in ourselves. Conversely, most of us find the bias exhibited by other people to be so obvious as to be comical.

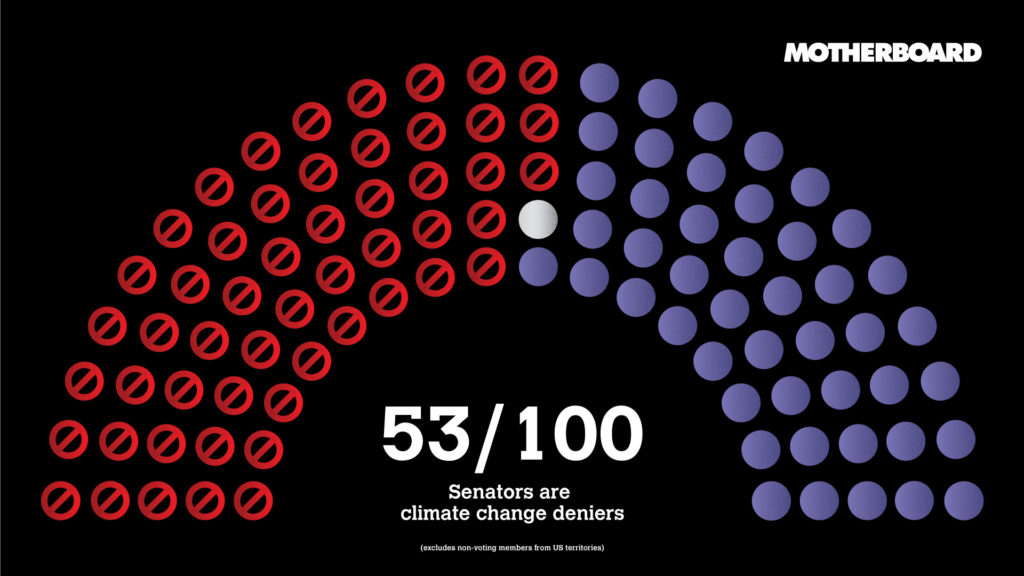

Just take climate change, for instance.

The people who are most afraid of its apparent consequences will cite it as the causal factor for any random warm day in the winter. “You see, Justin, climate change.” And yet, on the other end of the spectrum, you have the ‘deniers’ who will, like the Stanford death penalty study, overly emphasize some ambiguity in the climate models — so a weak argument on the other side. “You see,” they post on Facebook, “these guys can’t predict what will happen. I love petroleum. Burn baby burn.”

The funniest instance for me is when I go to an NFL football game. When basically any penalty is called on my home team Baltimore Ravens, the fans will boo in outrage. This applies equally to bad calls as it does to obviously correct calls. No matter how good the call, if it’s against our teams, we see it as fair.

So, yes, we are aware of confirmation bias in others. But, as these examples also show, the person under the influence is barely ever aware of that influence. The problem with the drunk driver is that he doesn’t believe he’s too drunk to drive.

And the nutrition field is no exception.

The plant-based crowd will post any epidemiological study showing a correlation between less meat and more plants with longer lifespans. Similarly, the carnivores will post articles that show that in this one study, meat didn’t have a negative effect. And just like religion and politics, the meat v. no meat debate is more than just confirmation bias. Deep within these arguments are issues of identity and group bias– the “us” versus “them” principle.

The key in all this is to remember this one message: I am no exception. “I” here referring to me, of course, but also referring to anyone reading this. The sad fact is that we are all under the influence of these biases all the time.

The good news is there might be actions we can take to minimize their threat.

How To Shrink Your Bias

It appears from the work of Nobel laureate, Daniel Kahenman, and the late Amos Tversky, we can’t turn off the triggers all together. These biases are here to stay. But there does seem to be some actions we can take to mitigate the biases. Most of the research I’ve seen points to three main strategies.

- Awareness

- Curiosity

- Measurement

Defense #1: Awareness

It would be a mistake, I think, after reading the above to simply avoid; being careful not to watch or read arguments that support what we already believe. But this risks the loss of information that both supports what we believe, and is correct.

The same logic works the other way (and might be worse, and more common). If we simply avoid all arguments that contradict our current beliefs– on the basis that our confirmation bias will incorrectly dispatch of them anyway– we risk missing ideas that are helpful in our pursuit of truth.

Psychologist Gary Klein worries about this kind of reaction and restates the goal more productively:

“We want to shift the mindset of diagnosticians (and ourselves) so that they wonder about anomalies instead of dismissing them.”

Klein prefers to categorize the problem of confirmation bias not as aspect of our defective thinking, but in a more positive light. That we typically think effectively, but sometimes we get fixated to an idea, and this can cause problems. This idea is known as “fixation.”

Klein and others start with the idea of plain awareness. Psychologists have found, for example, that we can be influenced in various ways by things like weather, but when their attention is drawn to it, it disappears. It’s like a doctor once told a friend of mine— ‘sometimes the diagnosis is the cure.’

But as Dr. Louise Raussmen has explained, awareness isn’t enough. After you identify a trigger, you must frequently and actively act against its negative impact. Which brings us to the next defense: curiosity

Defense #2: Curiosity

After we become aware of our bias, Klein advises to increase your ‘curiosity’ about these little triggers.

“The core of the strategy is to become more curious about [triggers]—the hints we can be noticing. That doesn’t mean chasing every [trigger] because that’s not realistic. Instead, it means trying to at least notice contrary indicators, perhaps just for a few seconds, and wonder what is causing those indicators.”

Others have suggested, and in limited scenarios shown, that after becoming aware of the bias, we postulate various different possibilities and explanations for a given problem. This is sometimes called creating the “counter-arguing self.”

For the meat v. plant issue, we might think: these are compelling studies, but perhaps they just suggest that people who decide to eat plant-based diets are healthier in other ways. Or maybe it’s that going to whole-food plants is always going to be better than say, what Wilks’ father and those Tennessee Titans were eating before– which looked veggie free. After all, no one is arguing that more vegetables is bad.

Conversely, if you are a pro-meat paleo gal, perhaps instead of saying, “this is all bias bullshit” (which many have said), perhaps you say– “ok this is potentially compelling data.” Maybe I will investigate further into what would happen if I ate slightly less meat and slightly more plants.

Defense #3: Measurement

Klein and others have than taken one further precaution.

Klein then recommends to start keeping score of those moments. Klein has seen this strategy work to great effect in his work with large hospitals.

“Once we become more curious about [triggers] we can try to keep track of how many [triggers] we are explaining away. If our initial diagnosis is wrong, we should be getting more and more signals that contradict it. There’s more and more to explain away. So that’s another leverage point we can use.”

*

THERE ARE MANY STRATEGIES LISTED— but they all center around the three step process of (1) noticing, (2) becoming curious and (3) measurement, then continuing with this process, continuously looking for that feeling of tightening in your stomach and then drawing up counter examples, looking for cracks in your current views.

Perhaps the reason that The Game Changers and other documentaries like it are converting people to a plant-based diet, is the very fact that these people are coming into it with open minds. Many put it on because they already suspect there might be something amiss with their current diet.

This is to say nothing of the correctness of the movie. It just shows that when you’re open to change, you then allow yourself the luxury of the ability to actually do it.

So What Did I Think?

I did end up watching the movie.

My thoughts on it are this: through the use of story, some emotional and inspiring examples (world-record setting and crazy physical feats), as well as some compelling epidemiological data, and a particularly persuasive report on erections, The Game Changers builds a compelling case for the health of the plant-based diet. (For now, let’s set aside the enviornmental and animal cruelty arguments).

I think whether or not you are a plant-based eater, the way you should take this evidence is the same— in proportion.

That is, if you’re a meat-eater, I wouldn’t necessarily change to plants on the basis of this documentary alone. I think you might use it as a reason to look more deeply into the research. Maybe experiment with a small change. One more stalk of broccoli per week, one less serving of meat. Then, of course, as I did, you’ll need to measure.

If you’re a plant-eater, I’d take caution.

There is a massive cognitive incentive to allow this documentary to stroke your propensity to think you are reasonable, good, and right. But I think it’s better to observe those feelings and ask yourself about them. Am I taking the evidence on its face, or taking an opportunity to congratulate my current beliefs?

Either way, we should all look at this as what it is: a well-made film that perhaps gives us reason to evaluate further the evidence and our behavior. Then we can make the decision. But the pause and reflection is crucial.

Besos.

2 Comments on “Why a Vegan Resisted Watching ‘The Game Changers’ (A Pro-Vegan Documentary) For So Long”

I had to look up epidemiological. I knew I didn’t know what it meant!

Good blog, Justin!! Im happy you finally watched The Game Changer. Did I have anything to do with your decision?

One thing I want to point out. Some of it was very hard to understand. Lots of words I didn’t understand. You are so smart! Can you replace some of the more difficult words with words that the”layman” can understand??

Other than that, it was great, just like you!

Love you,

The Momzy